Scythian Death mask

Scythian Death mask

The meaning of the name of the ancestor of the Scythians was also a common characterization of his nation, his descendants. Truth and trustworthiness above advantage, which strongly reminds of the

de Vere family motto. "the prince of truth" "the defender of the side of the sun god" This tradition goes back to the ancient tradition of northern sunworship, where the sungod was the god of truth and protector of mankind and was represented by the light of the sun, which enlightens us. the Scythian name of God was TAR.

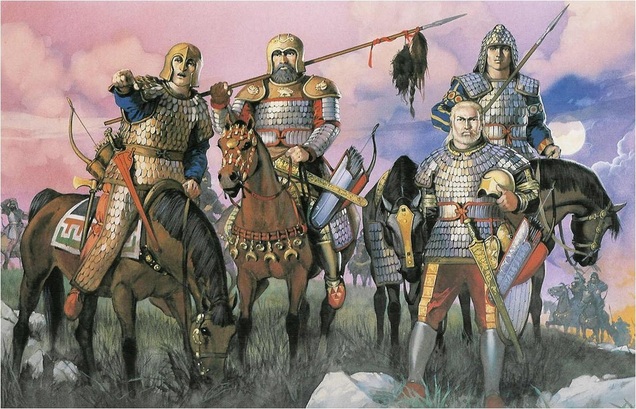

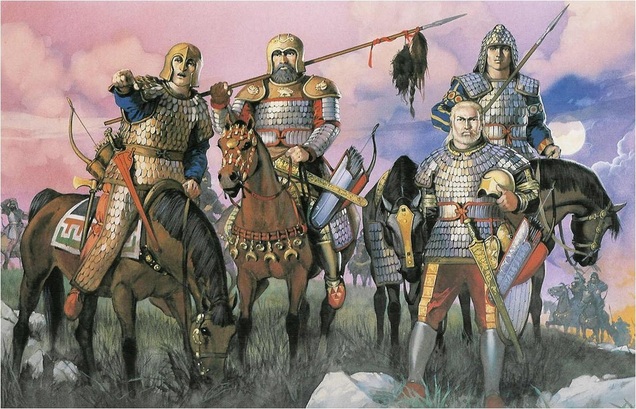

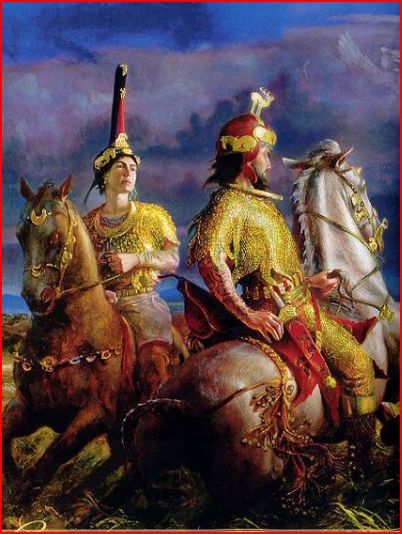

Fierce Scythians were known as Dragons for their heavy, segmented armour; they were the forefathers of medieval knights.

Fierce Scythians were known as Dragons for their heavy, segmented armour; they were the forefathers of medieval knights.

The Silk Road, itself, can be envisioned as a vast dragon.

Why not make your tribe's totem the biggest, baddest creature who's bones are in your hillsides?

Naturally, myths of dragons, dragon bones and dragon lords arose in tandem.

The crested dragon is the grand-daddy of T-Rex

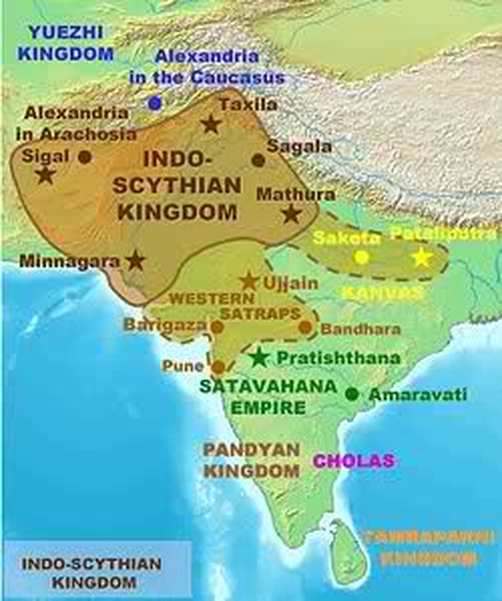

THE SAKA

THE SAKA

It seems that both nomadic and sedentary Iranians referred to themselves as Airyas; gradually, however, this word became a self-imposed designation for the settled Iranians only, who began to refer to their nomadic cousins in the East, i.e., Zoroaster's people, as the Saka, and some of those further west as SKUDRA [3][3]; the Saka probably did not call themselves exclusively by this name, some may have retained the use of the term Airya.

Many Saka tribes left the northern steppes intermittently to settle permanently in Central Asia, modern Afghanistan, and Persia; these tribes are the direct forebears of the imperial Western Iranians, the Medes, Persians and lastly, the Parthians;

Once converted to Zoroastrianism, however, such became their religious significance, that by the middle of the 1st millennium B.C., the centre of the faith was neither in the homeland of its founder, nor in any of the adjoining Eastern Iranian regions; it was firmly established on the western side of the great salt desert, amongst the people now called Western Iranians; from then onwards, Eastern Iran fades into the background; we now deal almost exclusively with Western Iran, and until very recently, were not even aware of the fact that Eastern Iran had played such a vital part in the genesis of the Iranian empires, and their great national faith; most scientific facts, such as, the recorded history and Near Eastern archaeological data, especially a large volume of deciphered inscriptions, relate to the four great Western Iranian empires of the Medes, Persians, Parthians & Sasanians; there is only a small volume of classical sources, and more recent archaeological data, which also deal with the nomadic Iranians of the northeast, i.e., those Saka warriors who remained in the steppes, and were never completely subdued by the settled Iranians of the imperial period; these warriors remained, nonetheless, a very formidable enemy of their settled cousins; not only did they conquer and rule the Median Empire for 28 years in the 7th century B.C., but they also defeated and killed Cyrus the Great, founder of the Achaemenian Empire, in the following century; a generation later, they were still engaging Darius the Great in many hard-fought battles; two hundred and fifty years later, however, they became the saviours of the Iranian culture and religion, and political integrity; they gradually pushed the Macedonians out of the Iranian homeland, and formed the Parthian Empire, which lasted for another 500 years.

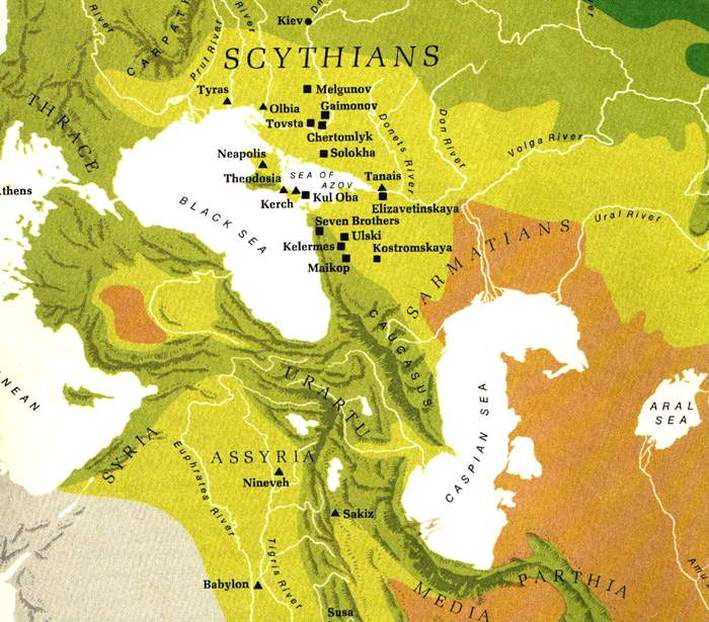

The nomadic Iranians of the north western steppes, however, especially those settled in Europe, are extensively covered by the classical writers; they are also attested in a very large number of archaeological excavations in Eastern Europe; these Iranian peoples are known in the West as Cimmerians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Alans, and finally Ossets; it must be emphasised that all these names refer to the successive migratory waves of the same people, who probably called themselves by a name derived from the word Airya, as the Alans did, and the Ossets still do.

CIMMERIANS

The earliest recorded nomadic western Iranians are the Cimmerians; they make their first appearance in Assyrian annals at the beginning of the 8th century B.C., where they are referred to as Gimmiri; they came down from modern Ukraine, and conquered eastern Thrace, and most of modern Turkey, being pushed westwards by another nomadic Iranian people, the Scythians (see below); they left behind a wealth of archaeological material, including a vast number of mound-burials in western Asia Minor; they later allied themselves with the Medes against the Assyrian Empire; the word GIMMIRI is attested in the Old Testament (Genesis I.x.12), as GOMER, the name given to one of Japhet's sons (see below, Scythian/Ashkenaz[4][4]).

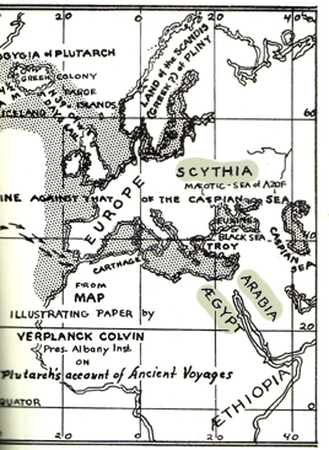

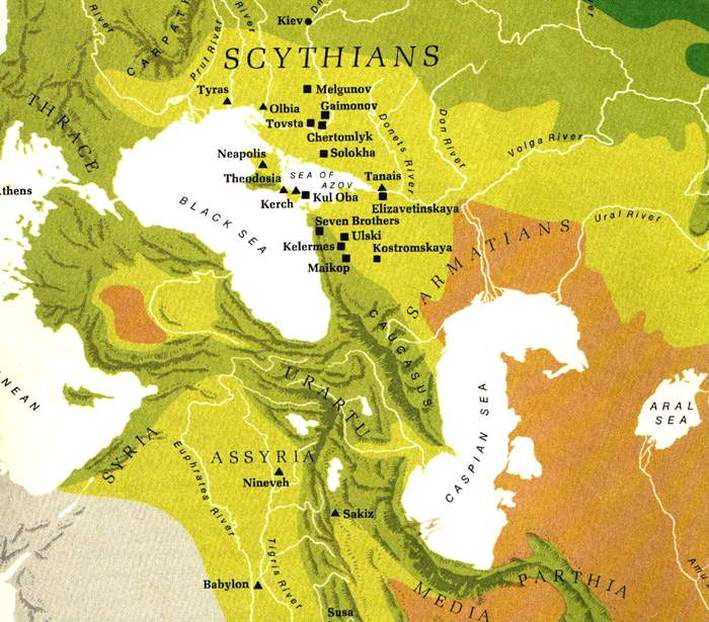

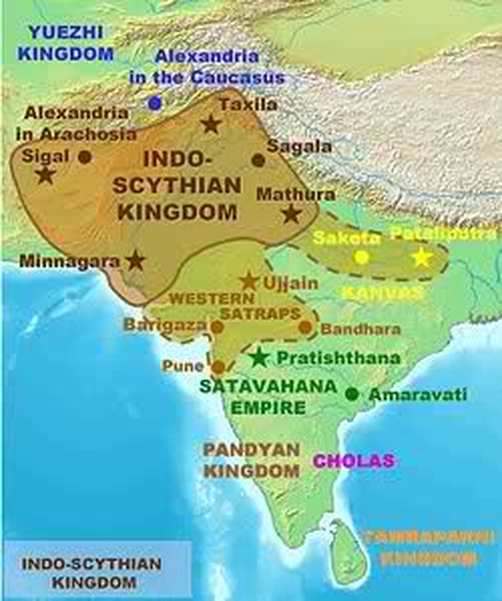

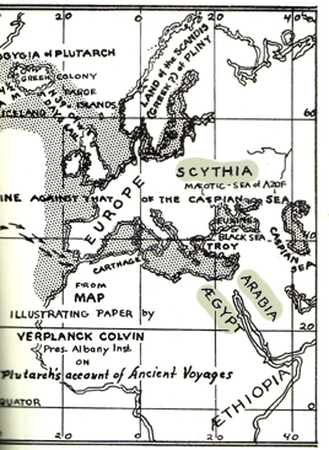

SCYTHIANS This is by far the most important, and enduring designation given by the classical sources to the nomadic Iranians of the steppes; the name refers to the entire non-sedentary Iranians, both in the West, and in the East (the Saka). Greek records place them in southern Russia in the 8th century B.C., however, recent archaeological evidence testifies that they, Cimmerians, and other Steppe Iranians may have been there far earlier. Greek geographers of the 4th century B.C. also credit the Scythians with inhabiting the largest part of the known world (map Red 16).

Like other Iranians, these nomads probably called themselves by the generic term "Airya"; this is testified inter alia by the native name of their descendants in the present day Europe (see below); it seems, however, that they, or at least some of their powerful clans, also called themselves "SAKA" in the East, and *SKUنA, SKUDA, or SKUDRA [5][5] in the West. SKUDA is believed to be related to the German word "SACHS", meaning a type of throwing-dagger which the eponymic Saxons used to carry and shoot with[6][6]; indeed, it is possible that like the historical Saxons, the Skuda derived their name from their ability to shoot. [cf. Franks].

Their first appearance in recorded history is again in the Assyrian annals, where they chase the Cimmerians, their own kinsmen, first out of Europe, then out of Asia Minor into the Median territory; in the 7th century B.C. they allied themselves with the Assyrians, and attacked the combined forces of the invading rebellious Median vassal king, Khshathrita (Phraortes in Greek, Kashtariti in Akkadian) and his Cimmerians allies; the Assyrians repelled the Medes, killing Phraortes, and routed the Cimmerians; the real victors, however, were the Scythians; for the next 28 years, now allied with their erstwhile enemy, the Cimmerians, they ravaged most of the Ancient Near East, including Media; later they allied themselves with Khshathrita's son, the Median emperor, Hvakhshathara II (Cyaxares in Greek, Uaksatar II in Akkadian), and the Babylonian king, Nabopolassar, taking Nineveh in 612 B.C. and destroying once and for all the mighty Assyrian Empire. (beginning of the Kurdish calendar)

The Scythians were called by the Assyrians Ashkuza or Ishkuza (A/Iڑ-k/gu-za-ai); as with the Gimmiri, this word also appears to have found its way into the Old Testament; one of Gomer's (Gimmiri) three sons, in Genesis I.x.12, is called Ashkenaz, which has given us the modern Hebrew word, Ashkenazi[7][7].

The Scythians were known by the Achaemenians, as SAKA and SKUDRA, by the Greeks, SKغTHIA (سê?èéل), by the Romans, SCYTHIAE (pron. SKITYAI), which has given us the English word SCYTHIAN; they lived in a wide area stretching from the south and west of the River Danube to the eastern and northeastern edges of the Taklamakan Desert in China; this vast territory includes now parts of Central Europe, the eastern half of the Balkans, the Ukraine, northern Caucasus, southern Russia, southern Siberia, Central Asia and western China.

Physiognomy

We know a great deal about their physical appearance; they were long-headed giants with blond hair and blue eyes; this well-known fact is attested by various classical sources [8][8], and by their skeletal and other remains in numerous archaeological excavations, which give a fairly detailed description of these ancient Iranians [9][9]; recently, a large number of their mummified corpses were discovered in western China; these mummies, which are extremely well-preserved in the arid conditions of the Taklamakan desert, are now on display at the museums of khotan, Urumchi, and Turfan in Sinkiang; they are dressed in Scythian costume, i.e., leather tunic and trousers, and are usually displayed in the sitting position, exactly as described by Herodotus; what is extra ordinary apart from their northern European features, however, is their gigantic heights, well over two metres as they are now, in spite of the natural shrinkage expected during the past thousands of years.

Equestrian skill

The Scythians, and other early steppe Iranians are believed to have been the first Indo-Europeans to use domesticated horses for riding (as opposed to eating); this theory has acquired fresh credibility after the recent discovery of horse skeletons at the Sredny Stog archaeological culture, east of the River Dniepr, a well-known pre-historical Scythian site in eastern Ukraine; these bones were identified as belonging to bitted, therefore, ridden horses dating to 4000 B.C., at least 2500 years older than the previously known examples.

More recent excavations east of the Ural Mountains credit them also with the invention of the first two-wheeled chariot [10][10]; such mobility, naturally, turned them into a formidable fighting force; they never willingly fought on foot, and used armour both for themselves and their mounts; they also developed the famous steppe tactic of faked retreat, and the "Parthian shot", shooting backwards while on mounted retreat; this tactic, named after their well-known descendants, the Parthians, requires an amazing skill and balance in the saddle, and a dazzling co-ordination of eyes, arms and breath without the support of stirrups.

Their women

In this unique pastoralist equestrian warrior society, women fought alongside their men; not only they were held in an equal status with men, but also periodically they actually ruled them;

this so called upside-down society both fascinated and horrified the male dominated Greek culture; later, the Romans expressed the same horror, when they encountered the Celtic and Germanic female warriors. Greek writers called the fighting Iranian women they met in the Ukrainian steppes, the Amazons; later Greek sources placed them further east, in northeastern parts of Iran.

This incredible social equality, at such an early age, is irrefutably attested, not only by a host of classical writers, but also by a wealth of archaeological evidence; in many mound- burials in the former Soviet Union, it is by no means unusual to find remains of women warriors dressed in full armour, lying on a war chariot, surrounded by their weaponry, and significantly, accompanied by a host of male subordinates specially sacrificed in their honour; nonetheless, these young Iranian warriors, as evidenced by the archaeological remains of their costumes and jewellery, do not seem to have lost their femininity; they remained "feminine as well as female" as a great contemporary German scholar puts it [11][11].

Archaeological excavations also testify to the amazing skill of these people in making jewellery; some of the finds are so dazzling in quality and advanced in technique that it is hard to imagine that they are produced by an unsettled, nomadic culture; we are indeed very fortunate that these early steppe Iranians practised elaborate funerary rituals and interred their treasures with their dead in huge impregnable burial mounds; hence, the vast majority of the steppe Iranians' artifacts known to the learned world is attributed to the Scythians. http://www.cais-soas.com/CAIS/Religions/iranian/Zarathushtrian/Oric.Basirov/origin_of_the_iranians.htmThe royal scythians who ruled altaic, uralic, iranic elements were the ugurs or yuezhi or tocharians (uyghurs,hungarians, bulgarians, chuvashes, tatars)

They are from 5 scythian folks the sabir, daha,chus and hun, avar.

And these folks are from sumerian, subartuan and elamite expansions to Caspian Areas (Khwarezm-turán)

The Middle Eastern civilizations are from Europe (Vinca, Trypillia, Kurgan cultures)

Ugur realms: Bactria, Parthia, Xiongnu (in Xiongnu lived the mongolic and manchu elements too) Kushan and next White hunnic Empire, Euro hunnia. Dragons have a long history in human mythology. How did the myth start? No one knows the exact answer, but some myths may have been inspired by living reptiles, and some "dragon" bones probably belonged to animals long extinct — in some cases dinosaurs, in others, fossil mammals. Starting in the early 19th century, scientists began to find a new kind of monster, one that had gone extinct tens of millions of years before the first humans evolved. Because the first fragments found looked lizard-like, paleontologists assumed they had found giant lizards, but more bones revealed animals like nothing on earth today. But early man most likely found plenty of fossils and stories arose around them.

Dragons have a long history in human mythology. How did the myth start? No one knows the exact answer, but some myths may have been inspired by living reptiles, and some "dragon" bones probably belonged to animals long extinct — in some cases dinosaurs, in others, fossil mammals. Starting in the early 19th century, scientists began to find a new kind of monster, one that had gone extinct tens of millions of years before the first humans evolved. Because the first fragments found looked lizard-like, paleontologists assumed they had found giant lizards, but more bones revealed animals like nothing on earth today. But early man most likely found plenty of fossils and stories arose around them.

http://www.strangescience.net/stdino2.htm

Regarding mythical creatures, Herodotus believed that some legends he heard preserved a kernel of genuine fact, and he played a role in spreading the legend of the griffin. Griffins, according to the nomads he interviewed, were four-legged and lion-sized, with wings and sharp beaks. What might the nomads have seen that prompted these myths? Modern paleontological digs in the region have revealed fossil skeletons of Protoceratops and Psittacosaurus dinosaurs. The nomads of his time may have seen similar skeletons eroding out of the sediments along the Silk Road. These weren't the only potential fossils mentioned in Herodotus's works. When in Egypt, he wrote, he was shown piles of "bones and spines." These may have belonged to spinosaurs, large Cretaceous reptiles with dorsal membraned spines, or to pterosaurs. And the giant skeletons of heroes he discussed may well have belonged to fossil mammals from the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs.

Regarding mythical creatures, Herodotus believed that some legends he heard preserved a kernel of genuine fact, and he played a role in spreading the legend of the griffin. Griffins, according to the nomads he interviewed, were four-legged and lion-sized, with wings and sharp beaks. What might the nomads have seen that prompted these myths? Modern paleontological digs in the region have revealed fossil skeletons of Protoceratops and Psittacosaurus dinosaurs. The nomads of his time may have seen similar skeletons eroding out of the sediments along the Silk Road. These weren't the only potential fossils mentioned in Herodotus's works. When in Egypt, he wrote, he was shown piles of "bones and spines." These may have belonged to spinosaurs, large Cretaceous reptiles with dorsal membraned spines, or to pterosaurs. And the giant skeletons of heroes he discussed may well have belonged to fossil mammals from the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs.

Herodotus mentioned at least one unambiguous fossil find. "I have seen shells on the hills," he wrote of Egypt. He reached a conclusion that is common today: The area "was originally an arm of the sea." Herodotus also ventured into the field of geology, guessing (inaccurately) that in the recent geologic past, Egypt had been a gulf of the sea. Although he was wrong about Egypt's geology, he was right in concluding that the world we live in changes over time, thanks to natural processes.

Scythians (skyty, skify). A group of Indo-European tribes that controlled the Southern Ukrainian steppe in the 7th to 3rd centuries BC. They first appeared there in the late 8th century BC after having been forced out of Central Asia. The Scythians were related to the *Sauromatians and spoke an Iranian dialect. After quickly conquering the lands of the *Cimmerians they pursued them into Asia Minor and established themselves as a power in the region. In the 670s BC they launched a successful campaign to expand into Media, Syria, and Palestine. They were forced out of Asia Minor early in the 6th century BC by the Medes, who had by then assumed control of Persia, and retreated to their lands between the lower Danube and the Don, known as *Scythia.

The bellicose Scythians were often in conflict with their neighbors, particularly the Thracians in the west and the *Sarmatians in the east. They faced their greatest military challenge around 513--512 BC, when the Persian king Darius I led an expeditionary force against them. By withdrawing and undertaking scorched-earth tactics rather than engaging in pitched battles, they forced the Persians to retreat in order to preserve their army. The event had a significant impact on subsequent Scythian development, for it confirmed their position as masters of the steppes and spurred on the political unification of the various tribes under the Royal Scythians. By the end of the 5th century BC the *Kamianka fortified settlement, near present-day Nykopil, had been established as the capital of Scythia.

The Scythians reached their apex in the 4th century BC under King Ateas, who eliminated his rivals and united all the tribal factions under his rule. He waged a successful war against the Thracians but died in 339 BC in a battle against the army of Philip 11 of Macedon. In 331 BC the Scythians defeated one of Alexander the Great's armies. Subsequently they began a period of decline brought about by constant Sarmatian attacks. They were forced to abandon the steppe to their rivals and re-established themselves in the 2nd century BC in the Crimea around the city of *Neapolis. There they regained part of their strength and fought several times against the *Bosporan Kingdom, and even managed to conquer Olbia and other Hellenic city-states on the northern Black Sea (Pontic) coast. Continued attacks from the Sarmatians, however, further weakened the Scythians, and an onslaught by the Germanic *Goths in the 3rd century AD finished them off completely. The Scythians subsequently disappeared as an ethnic entity through steady intermarriage with and assimilation into other cultures, particularly the Sarmatian.

The Scythians were divided into several major tribal groups. Agrarian Scythian groups lived in what is now Poltava region and between the Boh and the Dnieper rivers. The lower Boh region near *Olbia was inhabited by Hellenized Scythians, known as Callipidae; the central Dniester region was home to the Alazones; and north of them were the Aroteres. The kingdom was dominated by the Royal Scythians, a small but bellicose minority in the lower Dnieper region and the Crimea that had established a system of dynastic succession. Their realm was divided into four districts ruled by governors who maintained justice, collected taxes, and gathered tribute from the Pontic city-states. A separate coinage, however, was not developed by the Scythians until quite late in their history. Their administrative apparatus was in fact quite loose, and the various Scythian groups handled most of their affairs through a traditional structure of tribal elders. Over time Scythian society became increasingly stratified, with the hereditary kings and their military retainers gaining an increasing amount of wealth and power. Although most Scythians were freemen, slaves were common in the kingdom.

The Scythians inhabiting the steppe were nomadic herders of horse, sheep, and cattle. Those in the forest-steppe were more sedentary cultivators of wheat, millet, barley, and other crops. (Some scholars believe that those agriculturists may have been the predecessors of the Slavs.) Scythian artisans excelled at metalworking in iron, bronze, silver, and gold. The Scythians also engaged in hunting, fishing, and extensive trade with Greece through the Pontic city-states; they provided grains, livestock, fish, furs, and slaves in exchange for luxury goods, fine ceramics, and jewelry.

The Scythians' military prowess was in large measure the result of their abilities as equestrian archers. They raised and trained horses extensively, and virtually every Scythian male had at least one mount. They lavished care and attention on their horses and dressed them in ornate trappings. Saddles and metal stirrups were not used by the Scythians, although felt or leather supports may have been. The foremost weapon of a Scythian warrior was the double-curved bow, which was used to shoot arrows over the left shoulder of a mounted horse. Warriors commonly carried swords, daggers, knives, round shields, and spears and wore bronze helmets and chain-mail jerkins. The Scythians became a potent force not only because of their impressive array of weapons and training but also because they shared a strong underlying military ethos and belonged to a warrior society that bestowed honors and spoils on those who had distinguished themselves in battle. That ethos was reinforced by the common rite of adopting blood brothers and the use of slain foes' scalps or skulls as trophies or drinking cups.

Because of their generally nomadic or seminomadic existence the Scythians usually had relatively few possessions. Those they did have were often of exquisite quality and craftsmanship and established the Scythians' reputation in the ancient world as devotees of finery (see *Scythlan art).

The Scythians never developed a written language or a literary tradition. They had a well-defined religious cosmology, however. Their deities included the fire goddess Tabiti, followed by Papeus (the 'Father'), Apia (goddess of the earth), Oetosyrus (god of the sun), Artimpasa (goddess of the moon), and Thagimasadas (god of water). The Scythians did not build temples, altars, or idols to worship their deities, but they maintained a caste of soothsayers and believed strongly in witchcraft, divination, magic, and the power of amulets. Representations of Scythians and their gold ornaments suggest that they were the first people in history to wear trousers.

Scythian burial customs were elaborate, particularly among the aristocracy. A chieftain remained unburied for 40 days after his death. During that time his internal organs were cleansed, his body cavity was stuffed with herbs, and his skin was waxed. He was then parad'ed through his realm accompanied by a large retinue indulging in ostentatious lamentation. After 40 days he was interred in a large *kurhan (up to 20 m high) together with his newly killed favorite wife or concubine, household servants, and horses, as well as weapons, amphoras of wine, and a large cache of goods. Lesser personages had less elaborate funerals. A common practice was the erection of anthropomorphic statues (*stone babas) as grave markers.

For many years the memory of the Scythians was best preserved by Herodotus, who included a lengthy, basically factual account of them in his Histories. After the last Scythians had died out in the 3rd century AD, the tribes were largely forgotten. Interest in them was revived as a result of some spectacular finds in Scythian barrows, starting with the *Melgunov kurhan in 1763 The ensuing search for richer caches impeded archeological research on the more prosaic aspects of Scythian life until Soviet archeologists undertook work in that realm in the 2oth century. Scythian archeological sites in Ukraine include the *Bilske, *Kamianka, *Karavan, $Nemyriv, *Pastyrske, and *Sharpivka fortified settlements and the *Chortomlyk, *Haimanova Mohyla, *Kul Oba, *Krasnokutskyi, *Melitopil, *Oksiutyntsi, *Oleksandropil, *Solokha, *Starsha Mohyla, and *Zhabotyn kurhans.

The people who lived in Steppes were overwhelmingly horsemen. Many were at least semi-nomadic with herds of livestock. Nomadism explains why there were waves of occupants. These Steppe people, Central Eurasians, traveled to and mated with people in the peripheral civilizations. Herodotus is one of our main literary sources for the Steppe tribes, but he isn't terribly reliable. The people of the ancient Near East recorded dramatic encounters with the people of the Steppe. Archaeologists and anthropologists have supplied more information about the Steppes people, based on tombs and artifacts.

The people who lived in Steppes were overwhelmingly horsemen. Many were at least semi-nomadic with herds of livestock. Nomadism explains why there were waves of occupants. These Steppe people, Central Eurasians, traveled to and mated with people in the peripheral civilizations. Herodotus is one of our main literary sources for the Steppe tribes, but he isn't terribly reliable. The people of the ancient Near East recorded dramatic encounters with the people of the Steppe. Archaeologists and anthropologists have supplied more information about the Steppes people, based on tombs and artifacts.

1. CimmeriansThe Cimmerians (Kimmerians) were Bronze Age communities of horsemen north of the Black Sea from the second millennium B.C. The Scythians drove them out in the 8th century. Cimmerians fought their way into Anatolia and the Near East. They controlled the central Zagros in the early to mid 7th century. In 695, they sacked Gordion, in Phrygia. With the Scythians, the Cimmerians attacked Assyria, repeatedly.

Sources:

"Cimmerians" The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology. Timothy Darvill. Oxford University Press, 2008.

Marc Van de Mieroop's A History of the Ancient Near East

2. Huns .Contrary to contemporary standards, Hunnish women mingled freely with strangers and widows even acted as leaders of local bands. Hardly a great nation, they battled amongst themselves as often as with outsiders, and were as likely to fight for as against an enemy -- since such employment offered unaccustomed luxury.The Huns are best known for their fear-inspiring leader Attila, the Scourge of God.

3. Kushans"Mediaeval Commerce (Asia)" From The Historical Atlas by William R. Shepherd, 1926.Kushan describes one branch of the Yuezhi, an Indo - European group driven from northwestern China in 176–160 B.C. The Yuezhi reached Bactria (northwest Afghanistan and Tajikistan) around 135 B.C., moved south into Gandhara, and established a capital near Kabul.The Kushan kingdom was formed by Kujula Kadphises in c. 50 BC. He extended his territory to the mouth of the Indus so he could use the sea route for trade and thereby bypass the Parthians. The Kushans spread Buddhism to Parthia, Central Asia, and China. The Kushan Empire reached its peak under its 5th ruler, Buddhist King Kanishka, c. 150 A.D. Source:

Christopher I. Beckwith Empires of the Silk Road. 2009.

4. Parthians© http://www.cngcoins.com CNG CoinsThe Parthian Empire existed from about 247 B.C.-A.D. 224. It is thought that the founder of the Parthian empire was Arsaces I. The Parthian Empire was located in modern Iran, from the Caspian Sea to the Tigris and Euphrates Valley. The Sasanians, under Ardashir I (who ruled from A.D. 224-241), defeated the Parthians, thereby putting an end to the Parthian Empire.To the Romans, the Parthians proved a formidable opponent, especially after the defeat of Crassus at Carrhae. See: How did Crassus die?

5. Scythians(Sakans to the Persians) lived in the Steppes, from the 7th to the 3rd century B.C., displacing the Cimmerians in the area of the Ukraine. Scythians and Medes may have attacked Urartu in the 7th century. Herodotus says the language and culture of the Scythians was like that of nomadic Iranian tribes. He also says Amazons mated with Scythians to produce the Sarmatians. At the end of the fourth century, the Scythians crossed the Tanais or Don River, settling down between it and the Volga. Herodotus called the Goths Scythians.

Source:

Amazons in the Scythia: New Finds at the Middle Don, Southern Russia, by Valeri I. Guliaev World Archaeology © 2003 Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

More on the Scythians6. SarmatiansThe Sarmatians (Sauromatians) were a nomadic Iranian tribe related to the Scythians. They lived on the plains between the Black and Caspian Sea, separated from the Scythians by the Don River. Tombs show they moved west into Scythian territory by the mid-third century. They demanded tribute from Greek towns on the Black Sea, but sometimes allied with the Greeks in fighting the Scythians.

Source:

Jona Lendering

7. Xiongnu and Yuezhi of Mongolia The Chinese pushed the nomadic Xiongnu back across the Yellow River and into the Gobi desert in the 3rd century B.C. and then built the Great Wall to keep them out. It is not known where the Xiongnu came from, but they went to the Altai Mountains and Lake Balkash, where the nomadic Indo-Iranian Yuezhi lived. The two groups of nomads fought, with the Xiongnu triumphant. The Yuezhi migrated to the Oxus valley. Meanwhile the Xiongnu went back to harrass the Chinese in about 200 B.C. By 121 B.C. the Chinese had successfully pushed them back into Mongolia and so the Xiongnu went back to raid the Oxus Valley from 73 and 44 B.C., and the cycle began again. Source:

Library of Congress: Mongolia

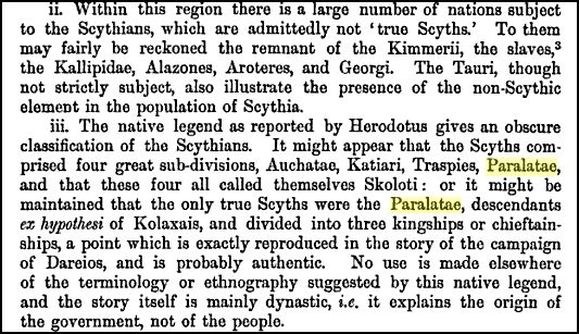

Herodotus on the CimmeriansHerodotus IV.6 lists the 4 tribes of the Scythians:

From Leipoxais sprang the Scythians of the race called Auchatae; from Arpoxais, the middle brother, those known as the Catiari and Traspians; from Colaxais, the youngest, the Royal Scythians, or Paralatae. All together they are named Scoloti, after one of their kings: the Greeks, however, call them Scythians. Lipoxais became the ancestor of the Auchatae, Arpoxais that of the Catiari and Traspians, and from Colaxais sprang the Royal Scythians or Paralatae. Sumerians, Scythians, and other Grail peoples

Sumerians, Scythians, and other Grail peoples

http://www.nexusmagazine.com/articles/starfire1.html

This is the article that got me interested in this subject in the first place!

http://www.whitestag.org/history/sumerian.html

and http://www.hunmagyar.org/hungary/myth/stag.html

The Hungarian White Stag Legends, and their connection to the Scythians, the land of Sumer,

and Enki, the Anunnaki lord who fathered humanity

http://www.giveshare.org/israel/arbroathdeclaration.html

The Declaration of Arbroath, in which St. Andrew speaks of the Scythian heritage of the Scottish people.

http://users.ev1.net/~gpmoran/mrn4.htm

A great site that discusses the archeological proof of the Scythian peoples' influence on the Celts.

http://www.electricscotland.com/history/wylie/vol1ch20.htm

Here is a site that also talks about the Scottish/Scythian connection,

and traces their possible migration path from their ancestral lands.

http://www.silk-road.com/artl/scythian.shtml

The expansion of the Scythians across Europe and Asia.

http://www.britam.org

This site discusses possible links between the Scythians and the Hebrews.

http://books.google.com/books?id=d83I2w3wbrIC&pg=PA13&lpg=PA13&dq=Paralatae&source=bl&ots=iqog5UnW_-&sig=nq8RVDHytVWfoRlz9nxTTd8rY3g&hl=en&ei=pQ2JTYW5DYHGsAOMy_CLDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&sqi=2&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Paralatae&f=false

http://books.google.com/books?id=d83I2w3wbrIC&pg=PA13&lpg=PA13&dq=Paralatae&source=bl&ots=iqog5UnW_-&sig=nq8RVDHytVWfoRlz9nxTTd8rY3g&hl=en&ei=pQ2JTYW5DYHGsAOMy_CLDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&sqi=2&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Paralatae&f=false

As Iljinskaja and Terenozhkin have established, the transition to the Scythian period has taken place here during the evolution of the Zhabotyn culture approximately in the middle of 7-th B.C. Thus, that fact is very important that findings of the Early-Scytian time are excavated in the right-bank forest-steppe up to the upper Dniester land. Due to the regular annual researches of the Lvov archeologists under L.Krushelnitska’s management, numerous settlements and burial grounds of the Late-bronze and the Late-iron time are discovered on the middle and upper Dniester land and in the Vorcarpathian. Among them are such remains which evidently show the gradual transition from the Chornolis to the Scythian culture, for example, the complex in the village of Neporotovo on the river Dniester in Chernovtsy Region: “In the area 6000 sq. m were excavated four settlements (Neporotovo I, II, III, IV), numerous separate remains and the remains of a burial ground. The findings and also the layers of the objects overlaping each other, enabled allocation of three chronological horizons: the upper –the Early-Scythian, the transitive - from the Pre-Scythian to the Scythian, and the lower which is synchronous with the Chornolis culture"(L.1993-1, 7).

The finds of the Early-Scythian time are revealed also in the Lvov Region - near to the village of Krushelnitsa in Skole Area and near the town of Dobromil on the river San (Krushelnitska L.1993-2, 226, 236). Scythian influences reach considerably further:

"The presence of the artifacts of Scythian type in the Central Europe (the authentic and made on Scythian samples) has allowed researchers to draw a conclusion that this territory was under influence of Scythian culture. The biggest concentration of finds of the Scythian type is observed in Transylvania and Hungary "(Popovich And. 1993, 250-251).

The Ukrainian archeologists as a whole recognize that the cultural continuity from the Pre-Scythian to the Scythian time is observed in the Ukrainian Forest-steppe first of all in the area of the spreading of the Chornolis culture and the finds of the Zhabotyn type which are considered as its continuation (Archeology of Ukrainian SSR, V 2, 1986, 50). The opinion about the succession of the Scythian culture in the Forest-steppe of the Dnieper Right-bank from local cultures does not cause objections even at supporters of Asian origin of the Scythian culture as a whole:

“A plenty of remains of the pastoral-agricultural population of the Scythian culture, which roots deeply go in local cultures of the Bronze Age, are concentrated in the Forest-steppe of the Right bank to the West from Dnieper” (Iljinskaja V.A., Terenozhkin A.I., 1983, 11 ).

Thus the following observation is important:

"The Scythian-Siberian barrow burial was spread in the Right-bank Forest-steppe ... Such ceremony, peculiar to early Scythians, has held steady on in the Forest-steppe of Right-bank up to the end of Scythian period " (Iljinskaja V.A., Terenozhkin A.I., 1983, 365).

This and other facts give the grounds to think that the Scythian culture was widespread to the Left bank of the Dnieper from the west, instead of from the east. Iljinskaja and Terenozhkin, supporters of its Asian origins, contradicted themselves when they spoke that in the Left-bank Ukraine the earliest remains of the beginning of the Iron Age are the settlements and the burial places of the second step of the Chornolis culture. Their occurrence has been caused by the consequence of the migration of a part of the population from the Dnieper Right banks at the end of 9-th or in the beginning of 8-th centuries B.C. Later a local version of the Scythian culture has been created on this basis. Other territory of the Left-bank Forest-steppe, on their supervision, has been populated later, at the beginning of the first half of 6-th century AD, and Scythian remains appear here already in a completely generated shape after Scythians have come back from assumed campaigns to For Asia(Iljinskaja V.A., Terenozhkin A.I.,1983, 366).

However, even supporters of the aboriginal theory did not occur that the Scythian culture could develop integrally on the basis of local cultures of the Western Ukraine. The opinion that the Scythian culture was brought here by newcomers whence from steppes dominates among scholars. Penetration of these carriers of the Scythian culture is supposed even till the territory of modern Hungary (Popovich I.1993, 282) and Germany. Scythian golden fish of the sixth century B.C. has been found in province of Brandenburg. This fact gives scholars grounds to say:

“With other objects of treasure, mostly, of gold, it documents the influence, and possibly the invasion, of Scythians, nomadic horsemen from the steppes north of the Black Sea, around 500 B.C.” (Dietrich Sahrhage, Johannes Lundbeck, 1992, 17).

Such opinions look surprising if to pay attention that the eldest remains of the Scythian culture in the village of Lahodiv (near to the city of Lvov) are dated by 5-th B.C., and further the chronological break begins to 1-st century AD when the period of the Lipetsk culture appears (Krushelnytska L.1993-2, 238). By Krushelnytska’s words, one can notice the same situation also "on the countries of the whole the forest-steppe Ukraine "(Ib.). Practically it means that the Late-Scythian culture had no place on these lands, but only the Early-Scythian one. Consequently, it looks illogical that the Scythian penetration in the Fore-Carpathian and further beyond the Carpathian Mountains began before the fullest flower of the Scythian culture in the steppes of the Northern Black Sea Coast.

Herodotus asserted that Scythians, coming from Asia, have superseded Cimmerians from the Black Sea Coast and pursued them even beyond the Caucasus. The area of Cimmerian cultures reaches beyond the Right bank of the Dnieper up to the Danube, therefore it is doubtful that Scythians, having arrived from the east, have superseded Cimmerians in the Transcaucasia. If Cimmerians receded before Scythians, they should escape somewhere beyond the Dnieper and further beyond the Danube, to the Balkans, but not to make the way through Scythians to the Derbent pass and further. In this case, Cimmerians attacks to For Asia should occur through the Balkans. The historical data testify that Cimmerians came in the majority from the Caucasian ridge and only any their part together with Thracians arrived to Asia Minor from Balkan Peninsula. This can take place only when Scythians came from the west, but not from the east.

Solving the question of the ethnic belonging of Scythians, it is necessary to pay attention to the fact of existence in the steppes near the Azov and the Caspian Seas in second half 1-st thousand two big states created by Bulgars and related to them Khazars. Bulgarian tribes have been incorporated in Great Bulgaria by one of the tribe leaders Kubrat into 635 and approximately at the same time Khazarian Khaganat started to develop too. Soon after Kubrats death, intense relations between both states led to disorder of Great Bulgaria. One Bulgarian horde migrated beyond the Danube where its leader khan Asparuh has created a new state - Danube Bulgaria while the second horde was got a part of the Khaganat. To the beginning of 8-th century Khaganat already possessed the large territory including foothills of Dagestan, the steppes about the river Kuban, the Sea of Azov, and a part of the Black Sea Coast, the most part of the Crimea. The young state had to conduct heavy struggle for existence with Arabs and consequently the most part of Bulgars has gradually departed on the north, in the basin of the river Kama where they have formed own state Volga Bulgaria in due course. (Pletneva S.A., 1986, 20-41). As we see, Bulgars should be very numerous people which history is traced on the ways of their migration from the Western Ukraine through the seaboard steppes up to the banks of the Kama. This numerous people which have to stay in the steppes of Ukraine in days of Herodotus therefore could not to be remained without the attention of this Greek historian. Hence, it is necessary to assume that Bulgars, at least, were among those tribes which are mentioned by Herodotus in his "Histories".

We know, that Proto-Bulgars moved to the right bank of the Dnieper from the end of 3-rd mill. B.C. First they have occupied only the steppe, but have promoted also in the forest-steppe strip later. This fact can to be testified by lexical coincidences between German and Chuvash languages (Stetsyuk V.,1998, 85-86). The hypothetical territory of Bulgar’s settlement should be somewhere to the south of the area of ancient Tuetons, that is in the basin of the upper Dniester, the rivers Vereschitsia, Zolota Lypa, Strypa. Bulgars stay in this territory can be proved by numerous toponymics. This theme has been considered in corresponding work more detailed (Stetyuk V., 2002, 13-20). Here it is possible to specify only that one the of congestions of Scythian toponymics is in the territory of the Cherepyn-Lahodiv group of archaeological remains which L. Krushelnytska binds with the Early-Scythian culture. On the whole, the greatest congestion of Bulgarian toponymics has been revealed on territory of the Lvov Region and further to the east up to the river the Hnyla Lypa though it is certified on all territory forest-steppe Rightbank Ukraine where it adjoins to the toponymics of Kurdish type. Thus Bulgarian toponymics lasts as the expressed chain up to Dnieper, passes it in the area of the river Vorskla’s mouth, further goes upwards the Vorskla, and then gradually becomes sparse. Also what is the most surprising, that the general area of Bulgarian and Kurdish toponymics mostly coincides with area the of the Chornolis culture together with the characteristic tongue on the Vorskla (see Fig.3). There is no doubt that exactly on this territory ancient Bulgars and Kurds lived in the close neighbourhood and this can be been displayed confirmed by numerous lexical parallels between Chuvash and Kurdish languages (see the previous chapter). As other ethnic groups were not present at the Rightbank Ukraine at this time, one may believe that creators of the ethnically not identified Chornolis culture could be only Proto-Bulgars and Proto-Kurds. Estimating of the proportional contribution of both ethnoses into this culture is difficult at present, but on all signs it seems to be that the leading role played Proto-Bulgars. Having taken into account the fact and the chronological frameworks of evolution of the Chernolis cultures to the Early-Scythian culture, one may go further to assume that Scythians should be identified with Bulgars and Kurds as creators of Early-Scythian culture in the Ukrainian Forest-steppe down to the Carpathian Mountains and the river San. According to toponimics, the nucleus of the Scythian culture began to arise on the banks of the left tributaries of the Dniester – the rivers Vereschitsia, Hnyla Lypa, Zolota Lypa, Strypa, Seret. Obviously, the well-known Scythian gold was extracted in the basin of these rivers as the numerous toponymics, which can testify former rich deposits of this metal, concentrates here (the Ukrainian root “zoloto” (gold) may be find in the names of the rivers Zolota Lypa, Zolota, the settlements of Zolochev, two villages of Zolochivka, of Zolotniks, of Zoloty Potik, of Ivane-Zolote, of Bilche-Zolote, of Zolota Sloboda).

Scythians and Druids

Scythians and Druids

The Tocharians depicted in the cave shrines of Takla Makan are red haired and wear the same conical hat, sometimes called a Phrygian cap. A variant of this was worn by Mithras, the intermediary god adopted by the Persians and featured in the Indian pantheon of the Asuras.

In monarchical dualism he is depicted as balancing the forces of increase and decrease, represented by the gods Ahura Mazda and Ahriman and some classical authors identified him with Jesus Christ. His headgear is also depicted as the hat worn by gnomes and dwarves.

Accompanying the depictions of the Tocharian Lords in these cave temples are examples of the language attributed to them - Tocharian A script - which looks remarkably like one of the scripts that Tolkien attributes to his Elven peoples. That the Tocharians are Scythian-Aryans themselves means that the devotional language used by their High-Kings and Queens might justifiably be called an Elven language, the tongue of Tolkien’s Sundered Elves of the East.

The second Gaelic word for ’vampire’ is Sumaire, which is pronounced shimarie, with the accent on the middle syllable - shim AR ri. Sumaire is translated as ’vortex’, meaning a whirlpool or spiral, a labyrinth: a sucker, a reptile (serpent or Dragon).

There is a clear link here with Sumeria and Anu’s mother Tiamat, the Dragoness of the deeps, and with Anu’s children Samael and Lilith, the forebears of the fairies. Various pictures of the latter two depict them as entwined around a tree, often the tree is Lilith herself, with Samael as the serpent or dragon resting in her branches as in Hebraic Iconography where Lilith is the Tree of knowledge in the Garden of Eden.

The Sumerians appeared first in Mesopotamia in 3500 BC. Prior to their emergence they were preceded by the Ubaid migrants from what is now southern Romania, from Carpathia and Scythia, who had fled south to escape the Black Sea flood of 4000 BC. Dated to about 5000 BC, archaeologists working in Tartaria in the UbaidTransylvania, discovered a ’tepes’ or Rath under which they found a fire-pit.

territory of

Buried amongst the ashes were the human remains of a cannibalistic sacrificial victim and two clay tablets. On these were inscribed the name of Enki (Samael), the number of Anu - 60 - and the image of a goat, Enki again, and a Tree - Lilith. In Hinduism Siva is the Goatherd of the Mountains.

The pictographic nature of the inscriptions convinced the archaeologists that the language was the forerunner of Sumerian and so they called it proto-Sumerian. Making it fairly obvious that the Sumerians were originally Ubaid Overlords from Central Eurasia.

Since the time of Herodotus, many have had their own ideas on the origins of the Scythians. Mallory (1989) noted that some thought that the origin lie in the west, in the region north of the Black Sea. Others, saw the Scythians, and Iranians in general, as originating in Central Asia, and even Siberia. Some have even thought that a multi-regional origin was more likely, with changes being cultural, rather than demographic.

Since the time of Herodotus, many have had their own ideas on the origins of the Scythians. Mallory (1989) noted that some thought that the origin lie in the west, in the region north of the Black Sea. Others, saw the Scythians, and Iranians in general, as originating in Central Asia, and even Siberia. Some have even thought that a multi-regional origin was more likely, with changes being cultural, rather than demographic. The first way to go at this, I feel, is to look at Karasuk. A culture that Mallory (1997), described as very mobile, compared to Andronovo, that is known more by their kurgan burials than their settlements. Karasuk is also seen as being highly influential and starting the animal art so common among the “Scythian” people (Keyser et al, 2009). Mallory (1997) even mentions the potential of the Karasuk to have a specific “proto-Iranian” identity. The influence of the Yenesei, and Slab Grave people cannot be underplayed (Mallory, 1997). Okunevo is thought to be a mix of Afanasievo and local Yeneseian groups (Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1979), in an area later within the Andronovo sphere, and this mixing may likely be the formation of the Karasuk culture within the Minusinsk Basin. Okunevo is thought to be the group that introduced realistic animal art to these later steppe pastoralists as well.

The first way to go at this, I feel, is to look at Karasuk. A culture that Mallory (1997), described as very mobile, compared to Andronovo, that is known more by their kurgan burials than their settlements. Karasuk is also seen as being highly influential and starting the animal art so common among the “Scythian” people (Keyser et al, 2009). Mallory (1997) even mentions the potential of the Karasuk to have a specific “proto-Iranian” identity. The influence of the Yenesei, and Slab Grave people cannot be underplayed (Mallory, 1997). Okunevo is thought to be a mix of Afanasievo and local Yeneseian groups (Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1979), in an area later within the Andronovo sphere, and this mixing may likely be the formation of the Karasuk culture within the Minusinsk Basin. Okunevo is thought to be the group that introduced realistic animal art to these later steppe pastoralists as well.

Scythian Death mask

Scythian Death mask

Fierce Scythians were known as Dragons for their heavy, segmented armour; they were the forefathers of medieval knights.

Fierce Scythians were known as Dragons for their heavy, segmented armour; they were the forefathers of medieval knights. THE SAKA

THE SAKA Dragons have a long history in human mythology. How did the myth start? No one knows the exact answer, but some myths may have been inspired by living reptiles, and some "dragon" bones probably belonged to animals long extinct — in some cases dinosaurs, in others, fossil mammals. Starting in the early 19th century, scientists began to find a new kind of monster, one that had gone extinct tens of millions of years before the first humans evolved. Because the first fragments found looked lizard-like, paleontologists assumed they had found giant lizards, but more bones revealed animals like nothing on earth today. But early man most likely found plenty of fossils and stories arose around them.

Dragons have a long history in human mythology. How did the myth start? No one knows the exact answer, but some myths may have been inspired by living reptiles, and some "dragon" bones probably belonged to animals long extinct — in some cases dinosaurs, in others, fossil mammals. Starting in the early 19th century, scientists began to find a new kind of monster, one that had gone extinct tens of millions of years before the first humans evolved. Because the first fragments found looked lizard-like, paleontologists assumed they had found giant lizards, but more bones revealed animals like nothing on earth today. But early man most likely found plenty of fossils and stories arose around them. Regarding mythical creatures, Herodotus believed that some legends he heard preserved a kernel of genuine fact, and he played a role in spreading the legend of the griffin. Griffins, according to the nomads he interviewed, were four-legged and lion-sized, with wings and sharp beaks. What might the nomads have seen that prompted these myths? Modern paleontological digs in the region have revealed fossil skeletons of Protoceratops and Psittacosaurus dinosaurs. The nomads of his time may have seen similar skeletons eroding out of the sediments along the Silk Road. These weren't the only potential fossils mentioned in Herodotus's works. When in Egypt, he wrote, he was shown piles of "bones and spines." These may have belonged to spinosaurs, large Cretaceous reptiles with dorsal membraned spines, or to pterosaurs. And the giant skeletons of heroes he discussed may well have belonged to fossil mammals from the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs.

Regarding mythical creatures, Herodotus believed that some legends he heard preserved a kernel of genuine fact, and he played a role in spreading the legend of the griffin. Griffins, according to the nomads he interviewed, were four-legged and lion-sized, with wings and sharp beaks. What might the nomads have seen that prompted these myths? Modern paleontological digs in the region have revealed fossil skeletons of Protoceratops and Psittacosaurus dinosaurs. The nomads of his time may have seen similar skeletons eroding out of the sediments along the Silk Road. These weren't the only potential fossils mentioned in Herodotus's works. When in Egypt, he wrote, he was shown piles of "bones and spines." These may have belonged to spinosaurs, large Cretaceous reptiles with dorsal membraned spines, or to pterosaurs. And the giant skeletons of heroes he discussed may well have belonged to fossil mammals from the Miocene, Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. The people who lived in Steppes were overwhelmingly horsemen. Many were at least semi-nomadic with herds of livestock. Nomadism explains why there were waves of occupants. These Steppe people, Central Eurasians, traveled to and mated with people in the peripheral civilizations. Herodotus is one of our main literary sources for the Steppe tribes, but he isn't terribly reliable. The people of the ancient Near East recorded dramatic encounters with the people of the Steppe. Archaeologists and anthropologists have supplied more information about the Steppes people, based on tombs and artifacts.

The people who lived in Steppes were overwhelmingly horsemen. Many were at least semi-nomadic with herds of livestock. Nomadism explains why there were waves of occupants. These Steppe people, Central Eurasians, traveled to and mated with people in the peripheral civilizations. Herodotus is one of our main literary sources for the Steppe tribes, but he isn't terribly reliable. The people of the ancient Near East recorded dramatic encounters with the people of the Steppe. Archaeologists and anthropologists have supplied more information about the Steppes people, based on tombs and artifacts. Sumerians, Scythians, and other Grail peoples

Sumerians, Scythians, and other Grail peoples

Scythians and Druids

Scythians and Druids