George Julius Poulett Scrope (10 March 1797 – 19 January 1876) was an English geologist and political economist as well as a Member of Parliament and magistrate for Stroud in Gloucestershire.

While an undergraduate at Cambridge, through the influence of Edward Clarke and Adam Sedgwick he became interested in mineralogy and geology. During the winter of 1816–1817 he was at Naples, and was so keenly interested in Vesuvius that he renewed his studies of the volcano in 1818; and in the following year visited Etna and the Lipari Islands. In 1821 he married the daughter and heiress of William Scrope of Castle Combe, Wiltshire, and assumed her name; and he entered the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1833 as MP for Stroud, retaining his seat until 1868.[1]

Meanwhile he began to study the volcanic regions of central France in 1821, and visited the Eifel district in 1823. In 1825 he published Considerations on Volcanos, leading to the establishment of a new theory of the Earth, and in the following year was elected FRS. This earlier work was subsequently amplified and issued under the title of Volcanos (1862); an authoritative text-book of which a second edition was published ten years later. In 1827 he issued his classic Memoir on the Geology of Central France, including the Volcanic formations of Auvergne, the Velay and the Vivarais, a quarto volume illustrated by maps and plates. The substance of this was reproduced in a revised and somewhat more popular form in The Geology and Extinct Volcanos of Central France (1858).[1] These books were the first widely published descriptions of the Chaîne des Puys, a chain of over 70 small volcanoes in the Massif Central.

Scrope was awarded the Wollaston Medal by the Geological Society of London in 1867. Among his other works was the History of the Manor and Ancient Barony of Castle Combe (printed for private circulation, 1852).[1]

Early life

On 10 March 1797, George Julius Thomson was born in London to "John Thomson of Waverley Abbey, Surrey, and his wife, Charlotte"[2] and was baptized under this name a few months later. John Thomson was the head of a successful trading firm (one source alluded that it was Roehampton and Austin Friars, London)[3] that had dealings with Russia. His wife, Charlotte, was the daughter of well-to-do Doctor John Jacob of Salisbury.

George was the second son of John and Charlotte. Charles was the firstborn. The two brothers maintained a close friendship until Charles' "untimely death"[4] in a riding accident in Canada.[5] George and Charles cooperatively wrote Charles' autobiography.[6]

Not much has been documented about George's early and teen years, and his personal letters were left to his nephew Hugh Hammersley, but have been misplaced or destroyed. The sources reviewed by this researcher almost exclusively began with the circumstances of Thomson's birth and then resumed at his entry to Harrow at roughly thirteen years of age.

Education

Thomson received his education at Harrow School, a privately funded public school in the Harrow district of London.

After Harrow, Thomson was accepted to and enrolled at Pembroke College, Oxford in 1815. After a year he left Pembroke because he found that its science departments were lacking courses of interest to him. To sate his scientific appetite, he transferred to St John's College, Cambridge in 1816. Also, during this year Thomson "acquired the additional name Poulett, which his father had recently adopted from an earlier and aristocratic branch of his family."[2]

Once at St. John's, Thomson was introduced to Professors Edward Daniel Clarke and Adam Sedgwick who "gave him his lifelong interest in geology."[7] At the time these men were in the early stages of their careers, Clarke having been made the first professor of mineralogy within the field of geology at St. John's; Sedgwick being known for his attention to detail and his naming of certain sections of the geologic time scale including the Cambrian.[8] Thomson received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1821 in geology,[9] after having performed several years of fieldwork in continental Europe.

Social life]

After a comfortable courtship, Thomson was married to Emma Phipps Scrope on 22 March 1821.[10] She was the heiress of William Scrope (phonetically Scroop)[10] of Castle Combe, Wiltshire, which is north-east of Bath. She was also the great-granddaughter of Sir Robert Long, 6th Baronet. After a Royal Grant he assumed the name and arms of Scrope, in lieu of Thomson. The newly renamed George Poulett Scrope and his wife resided at Castle Combe Manor House, which the Scrope family had owned since the fourteenth century. Emma had been disabled after a riding accident soon after the marriage, and no children were born of their union. Scrope had extensive alterations made to the 17th-century house[11] and established formal gardens in the grounds.[12]

During the marriage, George Poulett Scrope kept a mistress, an actress known as Mrs. Grey, in a comfortable existence in London. Around the year 1838 their son was born, whom they called Arthur Hamilton. Scrope sent his illegitimate son to Eton College and Christ Church, Oxford for his education, eventually securing a commission for him. In 1856, Emma and George formally adopted Arthur as their son.

After Emma's death in 1866, Scrope sold Castle Combe and moved to Fairlawn, near Cobham, Surrey. The following year he married Margaret Elizabeth Savage, who was forty-four years his junior. Both Margaret Scrope and Arthur survived him.[2]

Study of volcanoes

During the time he attended St. John's College, Scrope had his first real experiences with what would become his geologic specialty – volcanoes – and what would be called igneous petrology. During the winter break of 1817 through 1818, George went on a vacation with his mother and father in Italy. In Naples he explored Mount Vesuvius and other areas of volcanism in the region.

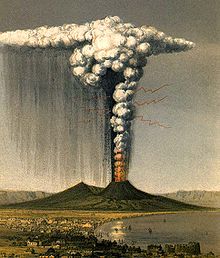

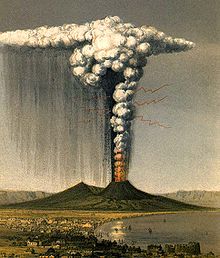

The Eruption of Vesuvius as seen from Naples, October 1822, drawn by Scrope in 1864

The Eruption of Vesuvius as seen from Naples, October 1822, drawn by Scrope in 1864

In 1825, Scrope became a secretary, jointly with Sir Charles Lyell, of the Geological Society of London. His later results from Auvergne were published for his 1826 election to the Royal Society. In 1853, Scrope was instrumental in the formation of and became the first president of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society, contributing heavily to its magazine.[2]

"[The] experience [in Naples] first aroused his lifelong fascination with volcanoes"[2] and soon after his marriage to Emma Phipps he went on a series of expeditions in Auvergne, France, Southern Italy, the Pontine Islands, Eifel, and other areas of notable current or past volcanism.[13] Scrope was present during the great Vesuvian eruption of 1822 which he deemed, according to his Geology and Extinct Volcanos of Central France, "by far the most important eruption of Vesuvius that ha[d] occurred during this century."[14]

Upon his return to England Scrope wrote, in an effort "to put [his] views clearly before the world as a contribution to sound knowledge and a step towards the demolition of ... errors still prevalent"[15] in the theories related to volcanism and Neptunism. This work, Considerations on Volcanoes, written in 1825, "is regarded as the earliest systematic treatise on volcanology [and] the first attempt to frame a ... theory of volcanic action and ... show the part ... volcanoes have played in the Earth's History."[16]

At the time of publication, however, Considerations was not very well received. Scrope commented in his Geology and Extinct Volcanos that Sir Charles Lyell wrote his first essay in the Quarterly Review for May 1827 reviewing the work, and was one of the few who gave it any public praise. Scrope couldn't resist giving Lyell a little barb when he commented on Lyell's career as a critic as following "the path of geological generalisation which he has since so successfully pursued."[14] Despite its initial poor reception, Considerations did help spark the curiosity of numerous other scientists and sent ripples in the Wernerian theory.

According to Abraham Gottlob Werner, the first phase of the Earth's development featured a great global ocean. This ocean was hot, steamy, and full of suspended sediment that eventually precipitated and formed bedrock. After this, the global ocean supposedly cooled and settled to such a degree that it began to subside and eventually conform to match the features seen today. During this time of subsidence, mountains were left behind as artifacts of erosion or a similar mechanism.

Scrope was not satisfied with this explanation of the presence and formation of rocks. He and many of his contemporaries were probably[weasel words] disturbed by the sense of utter finality, the idea that the earth was in a stage of winding down and would see no further development or change. George spent much time performing research locally and discussing the matter with colleagues.

In 1827, Scrope published his research from Auvergne in central France in his Geology and Extinct Volcanos of Central France. This work contained meticulously detailed drawings of basaltic column clusters, numerous panoramic views of valleys, and cross-sections of sedimentation and other types of stratigraphy. The work reads as a moving narrative, giving a very detailed road-map of analyzed data through the region.

In response to the release of this work, Sir Charles Lyell spearheaded an expeditionary force soon after to corroborate Scrope's findings and help build a case against Neptunism. After the group of natural philosophers returned, Lyell and Murchison confirmed the validity of Scrope's arguments. With the weight of their respective reputations and their findings behind him, Scrope ensured that "Werner's doctrine of the aqueous precipitation of basalt received from this work its death-blow."[17] Scrope wrote later in his Geology and Extinct Volcanos that "The Wernerian notion ... has since that date never held up its head."[14]

Since his beginnings as a geologist, George Poulett Scrope fostered a number of friendly relationships with some well-known natural philosophers. On his voyage and during the years since, Charles Darwin sent some letters to Scrope, checking certain geological observations and calculations he made, and made other general geology and scientific (in our modern terms) queries. These documents are mentioned by numerous sources, but were unavailable for review by this researcher.

During the mid-1820s, George Poulett Scrope came upon the greatest friendship of his life. Despite, and perhaps because of, Charles Lyell's objective appraisals of Scrope's first and certain subsequent works, the pair forged a strong friendship that lasted for the rest of their lives. While Lyell's uniformitarianist views were not to George's liking, he found solace in Professor Huxley's theories.

One author described the early nineteenth century, the time of George Poulett Scrope and Charles Lyell's early careers, as an "intellectual 'reign of terror'" which was the "consequence of the unreasoning prejudice and wild alarm excited by the early progress of geological inquiry."[13] Most attempts to explain the past using current processes as a reference was, rather than through calm argument, met by social stigma and intolerance. This can be seen by the treatment of Hutton's Theory of the Earth, Hall's meticulously kept records and experiments, and Playfair's Illustrations. These arguments had "come to be inscribed in a social Index Expurgatorius [and] might have seemed to be consigned to total oblivion."[13] The writer of Scrope's Obituary in the Royal Society's Proceedings believed that "science is indebted for boldly encountering and successfully overcoming this storm of prejudice ... [Scrope and Lyell] accomplish[ed] the removal of geology from the domain of speculation to that of inductive science."[13]

Based on Scrope's various arguments, he became a Huttonian in that he did believe that causes in operation currently were able to have produced past geological changes – the present is a key to explaining the past. He rejected aqueous origins and Von Buch's elevation-crater theory – which held that craters were caused by the buckling of the crust below them.

Because the friendship of Scrope and Lyell featured a "freedom of intercourse"[13] it was of great value to the pair in fighting conventional thought and its errors. Lyell wrote favourable reviews of several of Scrope's papers during the 1820s and 1830s, lending some of his considerable influence. Upon the release of Lyell's Principles of Geology, on parts of which he had extensive correspondence with Scrope,[10] George was "committed the congenial task of applying and driving home [their arguments]."[13] To this end, the first and second volumes of Principles of Geology were introduced by "appreciative and discriminative notices in the Quarterly [Review]"[13] which were written by his friend Scrope. The third edition of the series was also favourably reviewed by Mr. Scrope.

Political career

Around the year 1821, Scrope was made a magistrate and was affected with the hardships of the agricultural laborer. "Thenceforth his interest in economic and political affairs, tho [sic] it did not exclude his interest in geology, was unabated."[4] Scrope turned his considerable mind and talents of persuasion to the problems he saw.

An unusually articulate magistrate, Scrope communicated his views on current problems in letters to magistrate colleagues and in many pamphlets. Over the course of his life, George Poulett Scrope wrote more than seventy politically and economically charged pamphlets, earning him a common nickname of "Pamphlet Scrope."[4]

Scrope perhaps felt that his efficacy was limited if he remained only a local politician. In 1832, Scrope ran for the Parliamentary seat of Stroud, which he did not succeed in obtaining. However, one of the successful candidates, David Ricardo, shortly accepted the Chiltern Hundreds for reasons of family health,[18] and Scrope was returned for the seat unopposed.[19] He remained active in politics until 1867.

In the House of Commons, Mr. Scrope was not very vocal. He was, however, an avid writer. Professor Bonney, the original author of the Dictionary of National Biography's entry on Scrope, credited him with thirty-six papers on the subjects of volcanic geology and petrology. In his A Neglected English Economist: George Poulett Scrope, Redvers Opie estimated that if his entries to places such as the Quarterly Review, which were largely anonymous, were to be figured into the list of his total works, then "there are extant over forty books, pamphlets, and papers on political economy" concerning both practical and theoretical issues.[4]

The first economic publication that can be definitely attributed to Scrope is "A Plea for the Abolition of Slavery in England, as produced by an illegal abuse of the Poor Law, common in the southern counties"[4] which was written in 1829. Scrope was interested in the relationship between political economy and the other moral sciences.

Scrope heavily contributed to the Quarterly Review's Economic section. "Scrope's articles had three main themes: (1) the failure of accepted political economy to give sufficient weight to changes in aggregate demand and to the resulting possibility that under some situations an artificial demand could put to use resources … otherwise unemployed."[20] This essentially recommended that an artificially determined demand could stimulate available capital and the market.

Secondly, Scrope lamented the "evil effects of falling prices on total production as well as on the distribution of income and the need for banking reform to raise prices on the existing gold standard."[20] Scrope advocated that a tabular standard be instituted, allowing the banking system and the economy to keep up with the market. Jevons eventually aided in inserting the tabular standard, but gave large credit to Scrope and Lowe, who independently co-discovered it.

The third primary theme of Scrope’s articles to the Quarterly Review, according to Frank Whitson Fetter, is the "fallacies of Malthusian population doctrine and of the current proposals for sweeping reform of the poor laws that were based on the acceptance of the Malthusian view [that they be administered to] discourage population increase."[20] Scrope was an opponent of Ricardo's Malthusian ideas as well. Ricardo was an accomplished economist and a Member of Parliament for Port Arlington during the years 1819-1823.[21]

Scrope rejected Ricardo's definition of "rent theory" which was, according to the Wikipedia entry under Ricardo's name (cited below), "the difference between the produce obtained by the employment of two equal quantities of capital and labor."

The model for this theory of rent essentially stated that while only one grade of land is used for agriculture, rent will not exist, but when multiple grades of land are being utilized, rent will be exacted on the higher grades and will increase with the rise of the grade. "As such, Ricardo believed that the process of economic development, which increased land utilisation and eventually led to the cultivation of poorer land, benefited first and foremost the landowners because they would receive the rent payments either in money or in product."[21]

To his Principles of Political Economy, deduced from the Natural Laws of Social Welfare, and applied to the Present state of Britain he prefixed it as a "Preliminary Discourse on the coincidence of the rights, duties and interests of man in society" in an effort to define "the true scope and limits of political economy, and also of establishing a ground-work of axiomatic principles with respect to the rights of individuals and the duties of governments."[4] He felt that up to that point, such an endeavor had not whole-heartedly been made.

Opie wrote that the pages devoted to natural principles "breathe the spirit of the eighteenth century," and can be seen in his fondness for Butler and Hume.[4] Scrope was anti-anarchist and refused to allow certain extreme interpretations of "natural law" philosophy to lead him to it. And just as he avoided the finality of the Wernerian system, so too did he reject the "Panglossian stagnation which makes all things which are, eternal."[4] Scrope, however, avoided the other extreme which was state paternalism.

To counter arguments against these positions, he repudiated "whatever is, is right," if applied to actions of man or to justifications for existing institutions and their practices. Scrope felt that it was generally assumed that physical and mental satisfaction and happiness of man "'may be most materially influenced by his social arrangements and these arrangements are susceptible of great and indefinite … improvement.'"[4]

To George Poulett Scrope, the primary aim or goal in forming institutions should be to see to "'the greatest happiness of the greatest number [of parties].'"[4] Scrope did not accept another utilitarian tendency in thought that "'every action of man has necessarily a selfish motive.'"[4]

While it is true that Scrope studied political economy, which examined the impact of production and distribution of wealth and the happiness of those parties involved, he was "frankly interested in welfare economics, altho [sic] aware of the indefiniteness of the end,"[4] using the available facts, vague though they may be, to make generalizations possible for the masses of data involved. The principles of this science are made up of things deducted from axioms relative to the emotions and actions of men. These actions, to George Poulett Scrope, are to be gleaned from observation of experience. Scrope made numerous appeals to experience in his discussions of natural rights.

To Scrope, the general welfare was always in the back of his mind. "The right of property depends upon the 'principle of utility' which is itself … a generalisation per enumerationem simplicem."[4] The same is true of the foundations of "free labour and free disposal of its produce."[4] So while he saw that experience teaches that "aggregate production increases with the progress of division of labor … it also teaches that men will move to the point of maximum return for their effort."[4]

These concepts allow interesting interpretations to take place. Scrope followed the chain of experience to the conclusion that if the various parties involved are "left free to settle terms with each other" there will result a fair distribution of their claims on the joint produce.[4] Thus the parties involved can, in this way, attempt to avoid a situation which currently may be associated with John Nash's equilibriums, where the squabbling of both parties minimizes the gains on either end. The outcome of these situations, if left to their course, may, so Scrope implies, reach a social optimum (another current term) where all parties involved seek to have secure gains on both sides – for the greater good.

Scrope recognized the underlying self-interest in humans and realized that in the exercise of freedom of individual action, "'the unerring instinct of self-interest' has played its part in constructing a society more complexly coöperative than could be achieved by mortal design … [thus] Institutions must work with and not against the operation of self-interest" for society to thrive.[4]

With regards to poverty, Scrope seemed to prefer a "let's grow more food now and worry about declining population later" stand. To help this along, Scrope advocated emigration to the various British colonies as the strongest solution to the problem. He was, however, criticized for "treating emigration as a panacea for all social ills."[2]

Although Scrope did not have a particularly active political life, his brother Charles Thomson did. With much advising behind the scenes, Charles rose to political prominence and was eventually made Lord Sydenham. As part of his new duties, he was engaged in much economic and political discourse, for which he had quite a sound mind. He was responsible for implementing the Union Act in 1840, which united Upper Canada and Lower Canada as the Province of Canada. Eventually Charles became Governor General of Canada until his death in 1841.[22]

To his constituents, George Poulett Scrope was deemed an "enlightened [aristocratic] landlord and a compassionate magistrate" and nationally he attacked the current poor laws and Malthusian doctrine.[2] He expressed the view that the proper goal of the economist was to "promote social welfare, using the generation of wealth" as a means to this end.[2]

Later life

In his later years, Scrope began to withdraw from political life. His "decaying strength and increasing blindness compelled him to [retire]"[13] and during this time he released new editions of earlier works. During these years he gave counsel and kind words, in addition to helpful hints in research methodology and direction, to many young geologists. Lyell was also stricken with progressive blindness, bringing another ironic note to the pair's friendship.

Scrope received numerous accolades for his ventures in the fields of geology, politics, and history. His history of Castle Combe, written in 1852, is still accepted as an important work in such scholarship, and numerous pleasant comments regarding it were made in various Stroud and local media. Scrope also penned definitive biographies and analyses on local and national British figures during his lifetime, earning him honorable mention in numerous related publications. In 1867, for his groundbreaking work in geology, the Geological Society of London awarded George Poulett Scrope the Wollaston Medal – their highest award.[2]

The death of Lyell, his lifelong best friend, left him a broken man and he soon followed on 19 January 1876. Judd, in his Academy obituary of George Poulett Scrope, wrote that "born within a few months of one another, their deaths were separated by less than a year; 'lovely and pleasant in their lives, in their death they were not divided.'"[17] Many would agree with Judd's statement that Scrope was an earnest worker in the task of "establishing the science of geology on a philosophical basis."[17]

References

7

- ^ Jump up to:a b c

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Scrope, George Julius Poulett". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 485.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Scrope, George Julius Poulett". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 485.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Rudwick, Martin. "Scrope, George Julius Poulett." Oct 2007, 2008. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- ^ Burke, Sir Bernard. A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland. Harrison, Pall Mall: London. 4 ed. Part II. 1863, p. 1347.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Opie, Redvers. 1929. "A Neglected English Economist: George Poulett Scrope." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 44, no. 1: 101-102-137, p. 102.

- ^ Notices on Lord Sydenham's Death (1841). The Examiner, p 37-39. Toronto.

- ^ Scrope, George P., and Sydenham, Charles Edward Poulett Thomson. Memoir of the Life of the Right Honourable Charles, Lord Sydenham, G. C. B. : With a Narrative of his Administration in Canada. London: J. Murray, 1844.

- ^ Opie, p. 102.

- ^ Rudwick, Martin. Nov. 1974. "Poulett Scrope on the Volcanoes of Auvergne: Lyellian Time and Political Economy." Article in The British Journal for the History of Science: Cambridge University Press and the British Society for the History of Science, 44, no. 3: 205-242, p. 207.

- ^ "Thomson (post Scrope), George [Julius Duncombe] Poulett (THN816GD)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Page, L.E.. ed. 1970-1990. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Scribner, p. 261.

- ^ Historic England. "The Manor House Hotel (1199055)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Summerhouse in Italian Garden north east of Manor House Hotel (1363579)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h N/A. 1876-1877. "Obituary Notices of Fellows Deceased." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. v.25: i-ii-iv.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Scrope, George P. The Geology and Extinct Volcanos of Central France. New York: Arno Press Inc., reprint 1978.

- ^ G., A.. "George Poulett Scrope, F.R.S.." Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 27 January 1876.

- ^ "Scrope, George Julius Poulett." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Accessed 2008.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Judd, J. W. 1876. "George Poulett Scrope." Academy 9, no. Jan/June 1876: 102-103.

- ^ "Owing to the ill health in his family". The Times. 22 May 1833. p. 3. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ "Stroud Election". The Times. 31 May 1833. p. 5. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Fetter, Frank W. 1958. "The Economic Articles in the Quarterly Review and Their Authors, 1809-52." I. The Journal of Political Economy 66, no. 1: 47-48-64.

- ^ Jump up to:a b David Ricardo, Wikipedia entry.

- ^ Charles Poulett Thomson, 1st Baron Sydenham, Wikipedia entry.

- "Scrope, George Julius Poulett." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Accessed 2008.

- Burke, Sir Bernard. A Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Landed Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland. Harrison, Pall Mall: London. 4 ed. Part II. 1863.

- Commons, John R. 1990. Institutional economics: Its place in political economy. Transaction Publishers: NY.

- Conklin, Edwin G. 1951. "Letters of Charles Darwin and Other Scientists and Philosophers to Sir Charles Lyell, Bart. 1951." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 95, no. 3: 220-221-222.

- Fetter, Frank W. 1958. "The Economic Articles in the Quarterly Review and Their Authors, 1809-52." I. The Journal of Political Economy 66, no. 1: 47-48-64.

- G., A.. "George Poulett Scrope, F.R.S.." Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 27 Jan. 1876: 241–242. (According to the DNB article on Scrope, "A. G." represents Archibald Geikie.)

- Hughes. "SCROPE, George Poulett." Peerage.org website, 2008. Accessed 2008.

- Judd, J. W. 1876. "George Poulett Scrope." Academy 9, no. Jan/June 1876: 102-103.

- N/A. 1876-1877. "Obituary Notices of Fellows Deceased." Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. v.25: i-ii-iv.

- N/A. George Poulett Scrope, from a photograph. Database on-line. Available from Victorian and Edwardian Photographs – Roger Vaughan Picture Library, Geologists of the Geological Society of London (19th Century). Ref: PL 102.

- Opie, Redvers. 1929. "A Neglected English Economist: George Poulett Scrope." The Quarterly Journal of Economics 44, no. 1: 101-102-137.

- Page, L.E.. ed. 1970-1990. Dictionary of Scientific Biography. New York: Scribner.

- Rudwick, Martin. "Scrope, George Julius Poulett." Oct 2007. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- Rudwick, Martin. Nov. 1974. "Poulett Scrope on the Volcanoes of Auvergne: Lyellian Time and Political Economy." Article in The British Journal for the History of Science. 44, no. 3: 205-242. Cambridge University Press and the British Society for the History of Science.

- Scrope, George P. The Geology and Extinct Volcanos of Central France. New York: Arno Press Inc., reprint 1978.

- Scrope, George P. 1849. Suggested Legislation with a View to the Improvement of the Dwellings of the Poor. Piccadilly, London: James Ridgway.

- Scrope, George P. 1831. Extracts of Letters, From Poor Persons Who Emigrated Last Year to Canada and the United States. London: J. Ridgway; Chippenham, Wilts, Printed by R. Alexander.

- Scrope, George P. 1825. Considerations on Volcanos: The probable causes of their phenomena, the laws which determine their march, the disposition of their products, and their connexion with the present state and past history of the globe; leading to the establishment of a new theory of the earth. London: Printed and published by W. Phillips, George Yard, Lombard Street; sold by W. & C. Tait, Edinburgh; and Hodges & McArthur, Dublin.

- Scrope, George P., and Sydenham, Charles Edward Poulett Thomson. 1844. Memoir of the Life of the Right Honourable Charles, Lord Sydenham, G. C. B. : With a Narrative of his Administration in Canada. London: J. Murray.

- Williams, Henry S. 1863-1963. A history of science.

- Scrope, G. P. (1872). Volcanos: The character of their phenomena, their share in the structure and composition of the surface of the globe, and their relation to its internal forces. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

The Eruption of Vesuvius as seen from Naples, October 1822, drawn by Scrope in 1864

The Eruption of Vesuvius as seen from Naples, October 1822, drawn by Scrope in 1864