The title of Earl of Devon was created several times in the English peerage, and was possessed first (after the Norman Conquest of 1066) by the de Redvers (alias de Reviers, Revieres, etc.) family, and later by the Courtenays. It is not to be confused with the title of Earl of Devonshire, held, together with the title Duke of Devonshire, by the Cavendish family of Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, although the letters patent for the creation of the latter peerages used the same Latin words, Comes Devon(iae).[1] It was a re-invention, if not an actual continuation, of the pre-Conquest office of Ealdorman of Devon.[2]

Close kinsmen and powerful allies of the Plantagenet kings, especially Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV and Henry V, the Earls of Devon were treated with suspicion by the Tudors, perhaps unfairly, partly because William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475–1511), had married Princess Catherine of York, a younger daughter of King Edward IV, bringing the Earls of Devon very close to the line of succession to the English throne. During the Tudor period all but the last Earl were attainted, and there were several recreations and restorations. The last recreation was to the heirs male of the grantee, not (as would be usual) to the heirs male of his body. When he died unmarried, it was assumed the title was extinct, but a much later very distant Courtenay cousin, of the family seated at Powderham, whose common ancestor was Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (d.1377), seven generations before this Earl, successfully claimed the title in 1831. During this period of dormancy the de jure Earls of Devon, the Courtenays of Powderham, were created baronets and later viscounts.

During this time, an unrelated earldom of similar name, now called for distinction the Earldom of Devonshire, was created twice, once for Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy, who had no legitimate children, and a second time for the Cavendish family, now Dukes of Devonshire. Unlike the Dukes of Devonshire, seated in Derbyshire, the Earls of Devon were strongly connected to the county of Devon. Their seat is Powderham Castle, near Starcross on the River Exe.

The Earl of Devon has not inherited the ancient and original Barony of Courtenay or the Viscountcy of Courtenay of Powderham (1762–1835); nevertheless, his heir is styled Lord Courtenay by courtesy.

The first Earl of Devon was Baldwin de Redvers (c. 1095–1155), son of Richard de Redvers (d.1107), feudal baron of Plympton, Devon, one of the principal supporters of King Henry I (1100–1135).[5][6][7] It was believed by some that Richard de Redvers had in fact been created the first Earl of Devon, and although in the past this caused confusion concerning the numerical ordering of the Earls of Devon, the point is now more clearly settled in favour of Baldwin as the first.[8] Baldwin de Redvers was a great noble in Devon and the Isle of Wight, where his seat was Carisbrooke Castle, and was one of the first to rebel against King Stephen (1135–1154). He seized Exeter Castle, and mounted naval raids from Carisbrooke, but was driven out of England to Anjou, France, where he joined the Empress Matilda. She created him Earl of Devon after she established herself in England, probably in early 1141.

Baldwin de Redvers, 1st Earl of Devon, was succeeded by his son, Richard de Redvers, 2nd Earl of Devon, and grandson, Baldwin de Redvers, 3rd Earl of Devon, and the latter was succeeded by his brother, Richard de Redvers, 4th Earl of Devon, who died childless.[9][10][11]

William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon (d.1217) was the third son of Baldwin, the 1st Earl.[12] He had only two children who left children. His son Baldwin died 1 September 1216 at the age of sixteen, leaving his wife Margaret pregnant with Baldwin de Redvers, 6th Earl of Devon. King John (1199–1216) forced her to marry Falkes de Breauté, but she was rescued at the fall of Bedford Castle in 1224 and divorced from him, as having been in no true marriage. She is thus called Countess of Devon in several records. The fifth Earl's youngest daughter, Mary de Redvers, known as 'de Vernon', was eventually sole heiress of the 1141 Earldom. She married firstly, Pierre de Preaux, and secondly, Robert de Courtenay (d.1242), feudal baron of Okehampton, Devon.[13]

The 6th Earl was succeeded by his son, Baldwin de Redvers, 7th Earl of Devon (d.1262), who died without children.[14][15] His sister, Isabella de Forz, widow of William de Forz, 4th Earl of Albemarle, became Countess of Devon suo jure.[16] Her children predeceased her and she had no grandchildren.

Her lands were inherited by her second cousin once removed, Hugh de Courtenay (1276–1340), feudal baron of Okehampton, the great-grandson of Mary de Redvers and Robert de Courtenay (d.1242) of Okehampton.[17] He descended from Renaud de Courtenay, anglicised to Reginald I de Courtenay, of Sutton, a French nobleman of the House of Courtenay who took up residence in England after the conquest and founded the English branch of the Courtenay family, who became Earls of Devon in 1335. The title is still held today, by his direct male descendant.

Hugh de Courtenay was summoned by writ to Parliament in 1299 as Hugo de Curtenay, whereby he is held to have become Baron Courtenay.[18][19] However, forty-one years after the death of Isabel de Forz, letters patent were issued on 22 February 1335 declaring him Earl of Devon, and stating that he "should assume such title and style as his ancestors, Earls of Devon, had wont to do", by which he was confirmed as Earl of Devon.[20] Although some sources consider this a new grant the wording of the grant arguably indicates a confirmation and that he became thereby 9th Earl. Historic sources thus variously refer to him as either 1st Earl or 9th Earl, and the position cannot be decided either way due to the uncertainty of the surviving evidence. For the last years of his life he thus held two titles, 1st/9th Earl of Devon, by reason of the 1335 letters patent, and 1st Baron Courtenay, the title by which he had been summoned to Parliament in the years prior to the 1335 letters patent.[21]

The 1st/9th Earl was succeeded by his son, Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon.[22] Three of the eight sons of the 2nd/10th Earl had descendants a fourth, William Courtenay, was Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor. Sir Hugh Courtenay (1326–1349), KG, eldest son and heir of the 2nd/10th Earl, was one of the founding members of the Order of the Garter, but both he and his only son, Sir Hugh Courtenay (died 1374), predeceased the 2nd/10th Earl.[23] Sir Edward de Courtenay (died 1368/71), the third son, also predeceased his father, but left an eldest son, Edward de Courtenay, 3rd Earl of Devon (1357–1419), "The Blind", who inherited as the 3rd/11th Earl.[24] The 3rd/11th Earl's eldest son, Sir Edward Courtenay (died 1418), married Eleanor Mortimer, daughter of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March, but predeceased his father, leaving no children, and the 3rd/11th Earl's second son, Hugh de Courtenay, 4th Earl of Devon (d.1422) succeeded him as became 4th/12th Earl of Devon.[25][26] The 4th/12th Earl was succeeded by his son, Thomas Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (d.1458).[27]

The Wars of the Roses were disastrous for the Courtenay earls. The 5th/13th Earl's son, Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon (d.1461), fought on the losing Lancastrian side at the Battle of Towton (1461), was captured and beheaded, and all his honours forfeited by attainder. Tiverton Castle and all the other vast Courtenay lands were forfeited to the crown, later to be partially restored.

Second creation, 1469

Edward IV had made Humphrey Stafford, grandson and heir of Humphrey Stafford of Hooke, Dorset, his agent in the West Country.[28] On 17 May 1469, Stafford was created Earl of Devon, but was killed only three months later, having led royal forces against the rebel army of Robin of Redesdale, a deputy of the Earl of Warwick. Captured in the Battle of Edgecote, he was beheaded at Bridgwater on 17 August 1469. He left no children, and with his death the second creation of the earldom became extinct. He is known as the "Three Months' Earl".

Restored first creation, 1470

The Wars of the Roses continued and in 1470 the Lancastrian forces under Warwick prevailed, and Henry VI was restored to the throne. The 1461 attainders were reversed, and the earldom of Devon was restored to John Courtenay, 7th/15th Earl of Devon (d.1471), youngest brother of Thomas, the 6th/14th Earl.[29] There had been a middle brother also, Henry Courtenay (d.1469), who also perished in the Wars. When the Yorkists again prevailed in the following year, Edward IV had the legislation of Henry VI's second reign cancelled, and all of John Courtenay's honours were forfeited. A few weeks later, on 4 May 1471, he died fighting on the losing side at the Battle of Tewkesbury (1471), leaving no children. According to Cokayne, "on his death the representation of the ancient Earls of Devon (of the family of Reviers from whom the Courtenays had inherited it) and of the Barony of Courtenay (created by the writ of 1299) fell into abeyance between his sisters or their descendants, subject to the attainder of Edward IV (1461), which revived on that King's re-accession 14 April 1471".[30]

Third creation, 1485

Diagram showing the descent of the Courtenay Earls of Devon during the Wars of the Roses. Sir Hugh I Courtenay (d.1425) of Boconnoc was the link between the senior line made extinct following the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471 and the post-War creation of a new Earldom in 1485 by King Henry VII

Diagram showing the descent of the Courtenay Earls of Devon during the Wars of the Roses. Sir Hugh I Courtenay (d.1425) of Boconnoc was the link between the senior line made extinct following the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471 and the post-War creation of a new Earldom in 1485 by King Henry VII

Sir Edward Courtenay (d.1509), great-nephew of the 3rd/11th Earl, fought on the winning side at Bosworth on 22 August 1485, ending the Wars of the Roses and two months later the new King, Henry VII (1485–1509), by letters patent dated 16 October 1485, created Edward Courtenay Earl of Devon (or Devonshire), with the usual remainder to the heirs male of his body.[31] As the son and heir of Sir Hugh Courtenay (died 1471/2) of Bocconoc, Sir Edward Courtenay was the heir male of his family, his father being the son and heir of Sir Hugh Courtenay of Haccombe, younger brother of Edward de Courtenay, 3rd/11th Earl of Devon (d.1419), "The Blind". He united the Tiverton and Powderham lines of the family, having married Elizabeth Courtenay, a daughter of a younger son of the Powderham line. He died 28 May 1509, when the earldom was forfeited by the attainder in 1504 of his son and heir, William Courtenay (d.1511).

Fourth creation, 1511

William Courtenay (d.1511) hadit] married Princess Catherine of York, a younger daughter of King Edward IV, thereby exciting suspicions of disloyalty in Henry VII, who had him imprisoned and attainted for his supposed but unproven complicity in the conspiracy of Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk. However, during the reign of his son and successor King Henry VIII (1509–1547) William Courtenay was gradually forgiven. His lands were restored as far as was possible, and by letters patent of 10 May 1511 he was created Earl of Devon with remainder to the heirs of his body. He died suddenly of pleurisy a month later on 11 June 1511, leaving his only surviving son, Henry Courtenay (d.1539), to inherit the earldom.[32]

In December 1512 Henry Courtenay (d.1539) obtained by Act of Parliament the reversal of the 1504 attainder of his father, William Courtenay. In 1512 he thus inherited the earldom of Devon as held by his grandfather, having at his father's death the previous year already inherited the earldom conferred by patent on his father in 1511.[33] In 1525 he was created Marquess of Exeter by Henry VIII. However, in 1538 he was tried, convicted, attainted and beheaded by the same king for conspiring with the Poles and Nevilles against the government of Thomas Cromwell in the aftermath of the Pilgrimage of Grace. All his titles were forfeited by his attainder.[34]

Fifth creation, 1553[edit]

Edward Courtenay (d.1556), Henry Courtenay's second but only surviving son, was a prisoner in the Tower of London for fifteen years, from the time of his father's arrest to the beginning of the reign of Queen Mary (1553–1558), when he was released and created by her Earl of Devon. The patent differed from earlier patents in that it granted the earldom to his heirs male forever, rather than to the heirs male of his body. (This meant, as was decided in 1831, that the earldom could pass to his cousins, the Courtenays of Powderham, more specifically to William IV Courtenay (1527–1557), known retrospectively as the de jure 2nd Earl, which family had existed since the 14th century at that seat as prominent country gentry.) He was proposed as a prospective husband for his cousin Queen Mary, herself keen on the match, but is said to have refused her advances, after which Queen Mary married Philip II of Spain.[35] He was considered as a possible husband for her sister, the future Queen Elizabeth I. This made him a threat to Mary's reign. Moreover, he was implicated in Wyatt's rebellion, and was again locked up in the Tower. In 1555 he was permitted to travel to Italy, where he died at Padua in 1556, possibly due to poisoning. With his death, his male line was extinguished, and the earldom with it, or so it was considered until 1831.

Since there was no Earl of Devon, James I granted the title in 1603 to Charles Blount, 8th Baron Mountjoy, whose aunt had been the last Earl's mother. He died without legitimate children three years later, and the King gave (or rather sold) the Earldom to William Cavendish, 1st Baron Cavendish.

Meanwhile, the descendants of Sir Philip Courtenay (1340–1406), of Powderham, a younger son of the 2nd/10th Earl, having fought against the Courtenay Earls during the Wars of the Roses, lived under the Tudors as prominent country gentlemen.[36] The baronetcy was created in the Baronetage of England during the English Civil War in February 1644 for William VI Courtenay (1628–1702) de jure 5th Earl of Devon, of Powderham, Devon.[37] The third baronet gained the title Viscount Courtenay of Powderham in 1762.

In 1831, the senior living Courtenay of this line was William Courtenay, 3rd Viscount Courtenay (died 1835), an aged rake and bachelor, then living in exile in Paris, having fled a bill of indictment. Were he to die unmarried, the viscountcy would become extinct, while the baronetcy would be inherited by his third cousin, another William Courtenay (1777–1859), who was Clerk Assistant to Parliament and High Steward of Oxford University. William Courtenay (d.1859) persuaded the House of Lords that "heir male" in the last 1553 creation of the title had meant "heir male collateral", and that his cousin the 3rd Viscount was therefore also 9th Earl of Devon, and his ancestors the Courtenays of Powderham had been de jure Earls of Devon from 1556. William Courtenay (died 1859) duly succeeded his cousin as 10th Earl in 1835, and from him the present Earls are descended. (A madman, John Nichols Thom, claimed to be "Sir William Courtenay" in 1832, and stood for Parliament twice, as representative of the extreme Philosophical Radicals, and proclaimed his right to the Earldom. He organized an agricultural rising outside Canterbury in 1838, and was shot dead in the Battle of Bossenden Wood during its suppression.)

The inconvenience, since 1831, of having two Earls for the same county has been dealt with thus: The Cavendish Earls, who were elevated to a Dukedom in 1694, had been spelling their title Duke of Devonshire; the ancient Earls had usually been Earls of Devon. This is due in part to the differences between English and "law Latin", the language in which royal decrees were traditionally written. This has now become the difference between the two peerages, and it is convenient to call the Blount Earl (1603–06) Earl of Devonshire also.

The principal seat of the Earls of Devon until the expiry of the senior line in 1556 was Tiverton Castle in Devon, and as a subsidiary seat Colcombe Castle, Devon, both of which are now largely demolished. The Earls of Devon created after 1556, or in existence de jure, had occupied the manor of Powderham in Devon since the late 14th century, and Powderham Castle continues to be the principal seat of the present Earl of Devon.

Earls of Devon, First Creation (1141)[edit]

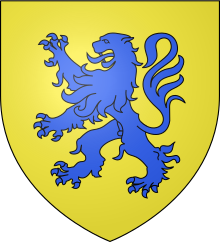

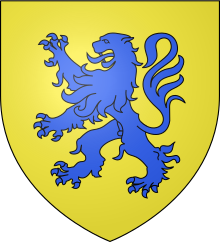

Arms of de Redvers, adopted at the start of the age of heraldry (c. 1200–1215), probably by William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon(died 1217), : Or, a lion rampant azure

Arms of de Redvers, adopted at the start of the age of heraldry (c. 1200–1215), probably by William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon(died 1217), : Or, a lion rampant azure

- Baldwin de Redvers, 1st Earl of Devon (c. 1095–1155)

- Richard de Redvers, 2nd Earl of Devon (died 1162) son

- Baldwin de Redvers, 3rd Earl of Devon (died 1188) son

- Richard de Redvers, 4th Earl of Devon (died c. 1193), brother

- William de Redvers, 5th Earl of Devon (died 1217), uncle

- Baldwin de Redvers (died 1216)

- Baldwin de Redvers, 6th Earl of Devon (1217–1245), grandson of the 5th Earl

- Baldwin de Redvers, 7th Earl of Devon (1236–1262) son

- Isabel de Redvers, 8th Countess of Devon (1237–1293), sister

Earls of Devon of the early Courtenay line[edit]

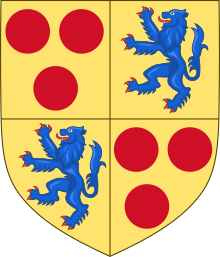

Arms of first Courtenay Earls of Devon: Or, three torteaux a label azure, as depicted (without tinctures) impaling Bohun on the monumental brass in Exeter Cathedral, Devon, of Sir Peter Courtenay (died 1405), 5th son of Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (died 1377)

Arms of first Courtenay Earls of Devon: Or, three torteaux a label azure, as depicted (without tinctures) impaling Bohun on the monumental brass in Exeter Cathedral, Devon, of Sir Peter Courtenay (died 1405), 5th son of Hugh Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (died 1377)

The ordinal number given to the early Courtenay Earls of Devon depends on whether the earldom is deemed a new creation by the letters patent granted 22 February 1334/5 or whether it is deemed a restitution of the old dignity of the de Redvers family. Authorities differ in their opinions, and thus alternative ordinal numbers exist, given here.[38]

- Hugh de Courtenay, 1st/9th Earl of Devon (1276–1340) (cousin; declared Earl 1335)

- Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon (1303–1377) (son)

- Edward de Courtenay (died bef. 1272)

- Edward de Courtenay, 3rd/11th Earl of Devon (1357–1419), "The Blind", (grandson of the 2nd/10th Earl)

- Hugh de Courtenay, 4th/12th Earl of Devon (1389–1422) (son)

- Thomas de Courtenay, 5th/13th Earl of Devon (1414–1458) (son)

- Thomas Courtenay, 6th/14th Earl of Devon (1432–1461) (son) (attainted 1461)

- John Courtenay, 7th/15th Earl of Devon (1435–1471) (brother) (restored 1469; in abeyance from 4 May 1471 to 14 October 1485, subject to revival of earlier attainder of 1461)

Earl of Devon, Second Creation (1469)[edit]

Earl of Devon, Third Creation (1485)[edit]

Original undifferenced Coat of Arms of the House of Courtenay: Or, three torteaux, as shown sculpted within a Garter on the chancel arch of St Peter's Church, Tiverton, Devon, being the arms of Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon, KG (died 1509)

Original undifferenced Coat of Arms of the House of Courtenay: Or, three torteaux, as shown sculpted within a Garter on the chancel arch of St Peter's Church, Tiverton, Devon, being the arms of Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon, KG (died 1509)

- Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (died 1509), KG, (forfeited at his death by son's attainder; restored 1512 to his grandson)

- Heir male to John Courtenay above; attainted 1484; restored to lands and honours then lost in 1485; if this was intended to restore the first Earldom, it was also forfeit 1538/9.

Earls of Devon, Fourth Creation (1511)[edit]

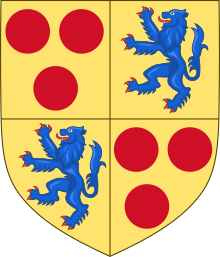

Arms of William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475–1511): Quarterly 1st & 4th, Courtenay; 2nd & 3rd Redvers, as sculpted on south porch of St Peter's Church, Tiverton, Devon, impaling the arms of King Edward IV, the father of his wife Princess Katherine

Arms of William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475–1511): Quarterly 1st & 4th, Courtenay; 2nd & 3rd Redvers, as sculpted on south porch of St Peter's Church, Tiverton, Devon, impaling the arms of King Edward IV, the father of his wife Princess Katherine

- William Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1475–1511) (attainted 1504; restored to the rights of a subject 1511; new creation two days later; died the next month without investiture, but buried as an Earl) son of Edward above.

- Henry Courtenay, 2nd Earl of Devon (1498–1539) KG; (heir to both 3rd and 4th creations after 1512); son of William above. (created Marquess of Exeter in 1525).

Marquess of Exeter, First Creation (1525)[edit]

Earls of Devon, Fifth Creation (1553)[edit]

Arms of later Earls of Devon, with the label azure further differenced by annulets or plates

Arms of later Earls of Devon, with the label azure further differenced by annulets or plates

- Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (1527–1556) (also restored in blood, but not honours, 1553; fifth creation dormant 1556†) son of Henry above. Died unmarried and without children.

Earls de jure, of Powderham[edit]

- William Courtenay, de jure 2nd Earl of Devon (1529–1557), of Powderham, sixth cousin once removed of Edward above,

- William Courtenay, de jure 3rd Earl of Devon (1553–1630)

- William Courtenay (died 1605), his eldest son, died before his father

- Francis Courtenay, de jure 4th Earl of Devon (1576–1638), his brother

- William Courtenay, de jure 5th Earl of Devon, 1st Baronet (1628–1702) (created 1644)

- Francis Courtenay (died 1699), his eldest son, died before his father

- William Courtenay, de jure 6th Earl of Devon, 2nd Baronet (1675–1735), son of Francis

- William Courtenay, de jure 7th Earl of Devon, 1st Viscount Courtenay (11 February 1709/1710 – 16 May 1762) (created Viscount Courtenay 1762)

- William Courtenay, de jure 8th Earl of Devon, 2nd Viscount Courtenay (30 October 1742 – 14 October 1788)

- William Courtenay, de jure 9th Earl of Devon (1788–1835), de facto 9th Earl of Devon (1831–1835), 3rd Viscount Courtenay (1768–1835; earldom retrospectively revived 1831†)

Earl's coronet worn by Charles Courtenay, 17th Earl of Devon (1916–1998) at the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1952. Displayed at Powderham Castle

Earl's coronet worn by Charles Courtenay, 17th Earl of Devon (1916–1998) at the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1952. Displayed at Powderham Castle

- William Courtenay, 9th Earl of Devon (1768–1835), died unmarried

- William Courtenay, 10th Earl of Devon (1777–1859), his second cousin: elder son of Rt. Rev. Henry Reginald Courtenay, Bishop of Exeter, who was the second son of Henry Reginald Courtenay, MP, who was the second son of Sir William Courtenay, 2nd Baronet

- William Reginald Courtenay, 11th Earl of Devon (1807–1888), his eldest son

- William Reginald Courtenay (1832–1853), his eldest son, died — unmarried — before his grandfather

- Edward Baldwin Courtenay, 12th Earl of Devon (1836–1891), his brother, died unmarried

- Henry Hugh Courtenay, 13th Earl of Devon (1811–1904), a priest; his uncle, second son of the 10th Earl

- Henry Reginald Courtenay, Lord Courtenay (1836–1898), his eldest son, died before his father

- Charles Pepys Courtenay, 14th Earl of Devon (1870–1927), his eldest son

- Henry Hugh Courtenay, 15th Earl of Devon (1872–1935), a priest; his brother

- Frederick Leslie Courtenay, 16th Earl of Devon (1875–1935), a priest; his brother

- Henry John Baldwin Courtenay, Lord Courtenay (b. and d. 1915), his elder son, died before his father

- Charles Christopher Courtenay, 17th Earl of Devon (1916–1998), Frederick's younger son

- Hugh Rupert Courtenay, 18th Earl of Devon (1942–2015), his only son

- Charles Peregrine Courtenay, 19th Earl of Devon (born 1975), his only son

The heir apparent is the present holder's only son Jack Haydon Langer Courtenay, Lord Courtenay (born 2009)

†: 1553 creation was with remainder to his heirs male whatsoever, so theoretically succeeded by his sixth cousin once removed; thus the 1831 revival was to the ninth member of the family with respect to said creation.

Courtenay Family Tree Medieval History The Manor of Powderham was mentioned in the Domesday Book. It came into the Courtenay family in the dowry of Margaret de Bohun on her marriage to Hugh de Courtenay, son of the first Courtenay Earl of Devon in 1325. The Courtenays had come from France in the reign of Henry II and had acquired considerable lands and power in the South West by judicious marriages to wealthy heiresses. They had castles at Okehampton, Plympton and Colcolme near Colyton. Margaret bore her lord eight sons and nine daughters, and from this marriage descends all the subsequent Courtenay Earls of Devon. She outlived him for a number of years, and left Powderham to her sixth son, Philip, in her Will. Sir Philip began building the Castle as we see it today in 1391. The building had the typical medieval long hall layout with six tall towers, only one of which remains today. His elder son Richard, who became Bishop of Norwich, and was Henry V's ambassador to France on his claiming the French throne, succeeded Sir Philip. He died at the siege of Harfleur 1415, and was succeeded by his nephew, another Sir Philip, who added the ‘Grange' accommodation for important visitors, the site of the current chapel. During the early 15th Century the senior branch of the Courtenay family were at feud with the family of Bonville for control of the West Country, but it appears that Sir Philip Courtenay of Powderham was friendly with Sir William Bonville of Shute (since his son William married Margaret Bonville) and this brought upon him the wrath of Thomas Courtenay, 5th Earl, who laid siege to Powderham Castle for seven weeks in 1455 but failed to gain possession. During the Wars of the Roses the senior branches of the Courtenay family adhered to the House of Lancaster - probably because the Bonvilles were on the other side - but there is evidence that Sir Philip Courtenay of Powderham was also on the side of the House of York. Thomas Courtenay, 6th Earl of Devon, was captured, attainted (i.e. his titles forfeited) and beheaded after the battle of Towton near York in 1461. His younger brother, Sir Henry of Topsham, regained some of the estates, but was debarred from inheriting the title due to the attainder, and was himself beheaded for treason in 1467; and the youngest brother, John, who was restored to the Earldom in 1470, was killed at the battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. This was the end of the senior line. Tudor Times 1485 - 1603 The third Earl had had a younger brother, Sir Hugh of Haccombe, who by his third wife had a son Sir Hugh of Boconnock, who also died of wounds following the Battle of Tewkesbury. His son, Edward, together with his son, William, fought on the side of Henry Tudor at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, and upon Henry's being crowned King Henry VII he recreated the Earldom of Devon (or Devonshire) in favour of Sir Edward Courtenay. King Henry married Elizabeth of York, the eldest daughter of Edward IV, and William Courtenay married her younger sister Katherine. This marriage brought upon him the jealousy of the King, and he was attainted in 1504 and imprisoned in the Tower of London. Upon the accession of Henry VIII in 1509 he was released, but his father dying that year, he was debarred from inheriting the Earldom due to his own attainder, which had not been reversed. King Henry VIII created him Earl of Devon in 1511, but he died before his investiture could be completed; nevertheless he was buried "with the honours of an Earl". Princess Katherine outlived him by a number of years, living at Tiverton Castle. They had a son, Henry, who succeeded as Earl of Devon and by his second wife had a son, Edward. King Henry named Henry Courtenay as his successor when he went to the Field of the Cloth of Gold, having as yet no heirs of his body, and created him Marquess of Exeter. Later they quarrelled and Henry Courtenay was accused of treasonable correspondence with his cousin Cardinal Pole, imprisoned in the Tower of London with his son, and attainted and beheaded in 1538. His son Edward, only 12 years old at the time, remained in the Tower until the accession of Queen Mary in 1553. He carried the Sword of State at her coronation in July, and was created by her Earl of Devon in September of that year, but appears to have been used as a pawn by the various factions of that time, and was again accused of treasonable correspondence, imprisoned again and finally exiled; he died in Padua, Italy in 1556 aged 30. Meanwhile at Powderham the succession had passed peacefully through several generations, and upon the death of Edward was held by Sir William Courtenay, the great-great-great-grandson of the second Sir Philip. Because of the wide remainder of the letters patent granting the Earldom to Edward Courtenay in 1553, the Courtenays of Powderham were entitled to inherit the title, but either this was not realised at the time, or else they decided it would be more prudent to lie low. Sir William was killed at the siege of St. Quintin in 1557, leaving a son aged only 4 years old. The English Civil War: The Siege of Powderham 1645 - 1646 In the 1640's Exeter was the South of England's second city after Bristol, and therefore of strategic importance. Exeter, and Powderham Castle, suffered terrible losses and damage in the Civil War (1642-6) between Charles I and Parliament. Within the City loyalties were divided (although Queen Henrietta Maria gave birth to her youngest daughter, Henrietta, there before retreating to France), but Powderham Castle remained a Royalist outpost faithful to King Charles. The Roundhead (pro-Parliament) faction triumphed at first in Exeter, but the Royalists held on at Powderham Castle. The Roundheads repaired the City walls; gun batteries were set up and ditches deepened. Nevertheless the Royalist armies eventually recaptured the city in 1643 and held it until early in 1646. In 1645 there was a major Parliamentarian assault on Powderham from across the River Exe. This was unsuccessful; but the Roundheads withdrew, gathered reinforcements and made a successful assault in January 1646. A triumphant Parliamentary force led by Sir Thomas Fairfax finally recaptured Exeter in 1646 as the Royalists holding the City had lost public support, illness was rife and morale low, forcing them to surrender. For Exeter, and for Powderham, the three years of bitter conflict was over. There were no family members at the Castle during the siege, but a Royalist garrison. The head of the family, Sir William Courtenay, was fighting on the Royalist side at the Battle of Bridgewater in Somerset, where he received bullet wounds to both legs. Powderham had been fairly badly damaged during the two sieges, and although it was not completely abandoned the family did not live there again during Sir William's lifetime. He had married Margaret Waller, heiress of Forde House in Newton Abbot. Margaret was the daughter of Sir William Waller, a Parliamentary general, and his wife Jane Reynell. Margaret had been brought up by her grandmother, Lucy, Lady Reynell since her mother died very shortly after she was born. It is said that William and Margaret were married so young that "they could not make thirty between them at the birth of their first child". They had a large number of children! It appears that the family lived at Forde House until Sir William's death in 1702 when his grandson, another William, inherited Powderham and his other properties. A Courtenay lord Georgian Period 1702 - 1837 Sir William Courtenay and his wife, Lady Anne Bertie, decided to restore Powderham Castle. They were probably responsible for transforming the long Great Hall into different areas, the Staircase Hall and the Marble Hall with two floors above it. Their son, Sir William, later the 1st Viscount Courtenay, inherited in 1735 and continued the improvements at Powderham. He was responsible for the wonderful rococo plasterwork on the hall and staircase walls, and it is his coat of arms over the doorway into the Marble Hall. He was one of the founding members of the Devon and Exeter Hospital in 1740. He was created Viscount Courtenay of Powderham in 1762 only ten days before his death. His son, the second Viscount continued with the improvements and additions at Powderham. He married Frances Clack in 1762 and had 14 children - 13 daughters and one son. He converted the chapel into a library and built another chapel near the northwest tower. He designed the Belvedere Tower in 1771. It was built using locally made bricks but timber from the New World. In 1788 his only son, another William, became the third Viscount Courtenay. He was responsible for the addition of the Music Room, designed by the famous architect James Wyatt, a design that included a carpet made in the newly formed Axminster Carpet Company. It was the biggest carpet they ever made, until the Prince Regent found out about it and insisted upon having a bigger one! Victorian Times - The Age of Reform 1830s - 1900 THE GOTHIC REVIVAL - CHARLES FOWLER In 1835 William Courtenay, son of the Bishop of Exeter who was himself the son of the younger brother of the First Viscount, inherited the title as the 10th Earl of Devon from his cousin the third Viscount Courtenay/9th Earl.of Devon. He lost no time in engaging the architect Charles Fowler to make Powderham "of a character consistent with an ancient castle". This he did very successfully, adding the State Dining Room, and at the same time changing the main entrance from the eastern side to the western, creating the viaduct and courtyard with the medieval style gatehouse. A raised garden was constructed on the eastern side facing the River Exe. The 10th Earl died in 1859 and the renovations which he had begun were completed by his son, William Reginald, 11th Earl, who put the linenfold panelling into the State Dining Room with the heraldic shields showing the descent of the French and English branches of the Courtenay family, and the families into which they married. During these renovations the chapel built by the 2nd Viscount was demolished, and in 1861 the medieval Grange was converted into a family chapel. The 11th Earl was a widower for more than twenty years before his death in 1888, when he was succeeded by his only surviving son, Baldwin, who, although he never married, is believed to have had several children. He died in 1891, and was succeeded by his uncle, Henry Hugh, who was Rector of Powderham, as the 13th Earl. The 13th Earl was eighty years old when he succeeded his nephew, and decided to continue to live in the Rectory (which he had built) and let the Castle to a family called Bradshaw. It was at this time that further alterations were made to the kitchens. ISAMBARD KINGDOM BRUNEL AND POWDERHAM CASTLE In 1844 The South Devon Atmospheric Board Gauge Railway was constructed through Powderham Park on its way from Exeter to Dawlish. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the famous Victorian designer, was the Chief Engineer and a business colleague of Lord Courtenay. Lord Courtenay, a member of the Atmospheric Railway Board, together with Isambard Kingdom Brunel had the foresight to select the flat estuary route through Devon for the railway, rather than the traditional route over the hills of Dartmoor. Brunel was also responsible for designing the road, which still runs from Powderham village to Starcross on the eastern side of Powderham deer park. The very first passengers were taken from Exeter to Dawlish on the Whit weekend of May 1846. In 1876 The South Devon Railway became part of The Great Western Railway and in 1892 the broad gauge line was changed to the standard gauge used today. The 20th Century Henry Hugh, 13th Earl, lived to be 92 and outlived his elder son by some six years. His eldest grandson, Charles Pepys Courtenay, 14th Earl, succeeded him in 1904. Powderham for the next thirty years was a bachelor household, as neither the 14th Earl, nor his younger brother Henry Hugh, who succeeded him as 15th Earl in 1927, ever married. The 15th Earl (who had been curate to his grandfather at Powderham and was Rector there until he succeeded to the Earldom) died in February 1935. His brother, the youngest of the three grandsons of the 13th Earl, succeeded to the Earldom, but only outlived his brother by four months, dying in June 1935 when he was succeeded by his only surviving son, Christopher, the 17th Earl, who was then aged 18. In July 1939 the 17th Earl, shortly after his 23rd birthday, married Venetia, Countess of Cottenham, the former wife of his second cousin. He also acquired two stepdaughters, Ladies Rose and Paulina Pepys. He was called up in September at the outbreak of the Second World War and served throughout in the Coldstream Guards, leaving his wife to run the Castle and the estate, which, however, had been much diminished by reason of the deaths of four Earls and the consequent death duties that had to be paid. His daughter Katherine was born in 1940 and his son, Hugh, in 1942. Between the two world wars agriculture, which provided the income for the estate, was in the doldrums and after the war several attempts were made to make Powderham and the estate pay. The Countess of Devon opened a domestic science school in the Castle, and a large house in Kenton called Court Hall was run for a while as a hotel. Neither of these ventures was successful in the long term. The 17th Earl took charge of the Home Farm (where the Country Store now is) and built up a herd of South Devon cattle. This was more successful, in that the cattle won many prizes, but ultimately it did not pay and the herd was dispersed. The 17th Earl died in 1998, aged 82 and having been Earl of Devon for sixty-three years. He was succeeded by his only son, Hugh Courtenay, who had been managing the estate for some years beforehand and whose wife, Diana, gave birth to three daughters, Rebecca (Beebs), Eleonora (Nell) and Camilla (Billa), and a son, Charles (Charlie). The family lived happily at the Castle during the 1990s and did much work to update the private side to become a modern(ish) home. All four children got married and provided Hugh and Diana with eleven grandchildren – Alice, Mimi, Tati, Lara, James, Harry, George, Willy-Billy, Tinka, Joscelyn and Jack. Very sadly, Hugh Courtenay died in August 2015 after only 17 years as Earl of Devon – a massive loss to the family, the Powderham community and Devon. He was succeeded by his son, Charlie. Charlie is a lawyer, who married Allison Joy (‘AJ’) Langer in 2004. Charlie and AJ have two children, Joscelyn and Jack. They are the 28th generation of the family to enjoy living in this remarkable family home.https://www.powderham.co.uk/stories

Diagram showing the descent of the Courtenay Earls of Devon during the Wars of the Roses. Sir

Diagram showing the descent of the Courtenay Earls of Devon during the Wars of the Roses. Sir  Arms of de Redvers, adopted at the start of the age of

Arms of de Redvers, adopted at the start of the age of  Arms of first Courtenay Earls of Devon: Or, three

Arms of first Courtenay Earls of Devon: Or, three  Original

Original  Arms of

Arms of  Arms of later Earls of Devon, with the label azure further differenced by annulets or

Arms of later Earls of Devon, with the label azure further differenced by annulets or  Earl's

Earl's